This is a guest blog by Dr. Clara Vaz Bauler is an associate professor of TESOL/Bilingual Education at Adelphi University, New York. Thanks to Clara for writing this and for the ideas shared here.

Typical, face-to-face learning environments offer advantages that online learning does not. The same can be said for online learning. This year, in the midst of the chaos of the pandemic and the rushed changes I had to make, I was pleasantly surprised by the many new opportunities my students and I had to communicate and share ideas. I could see all my students’ names and learn how to pronounce them by having students share on Flipgrid. This same video platform also allowed me and my students to share about ourselves without worrying about class time or period ending, as we could post videos and comments on our own pace. Above all, I could see and hear my students’ thinking in online discussions as ALL contributed their ideas.

As “Zoom classrooms” can be very frustrating with distracting noises, intrusion to privacy, and wifi interruptions, it is only natural that we blame the online medium for everything that went wrong in education during the pandemic. However, if we stop and ponder about what fundamentally constitutes the educational experience, especially the relationship between teachers and students, online spaces have much to offer. Online pedagogical practices have the potential to amplify student participation in ways that typical face-to-face environments cannot. So, it is imperative that we take this opportunity to engage in deep reflection about the possibilities technology can offer as we transition to physical buildings and face-to-face environments. Here are a few of my own reflections.

Multiple “Entry Points”

One of the main dilemmas I faced during remote learning was the use of cameras in my class. At first, I quickly condemned the online environment for my students’ apparent lack of participation. However, in digging deeper, I realized that the disruption of typical classroom practices aligned with the stressful conditions of the pandemic might have been a source of anxiety to my students. Instead of focusing on what my students could not do, I started rethinking how I was organizing my virtual synchronous meetings, paying close attention to alternative ways my students could actively engage. This reflection prompted me to reimagine what participation might look like given our difficult circumstances. I found out that helpful alternatives to cameras on included multiple “entry points” for participation based on choice and non-verbal modalities. I started experimenting with multimodal tools, using Jamboard to share emotions and brainstorm and Pear Deck to express ideas via drawing, labeling and polling.

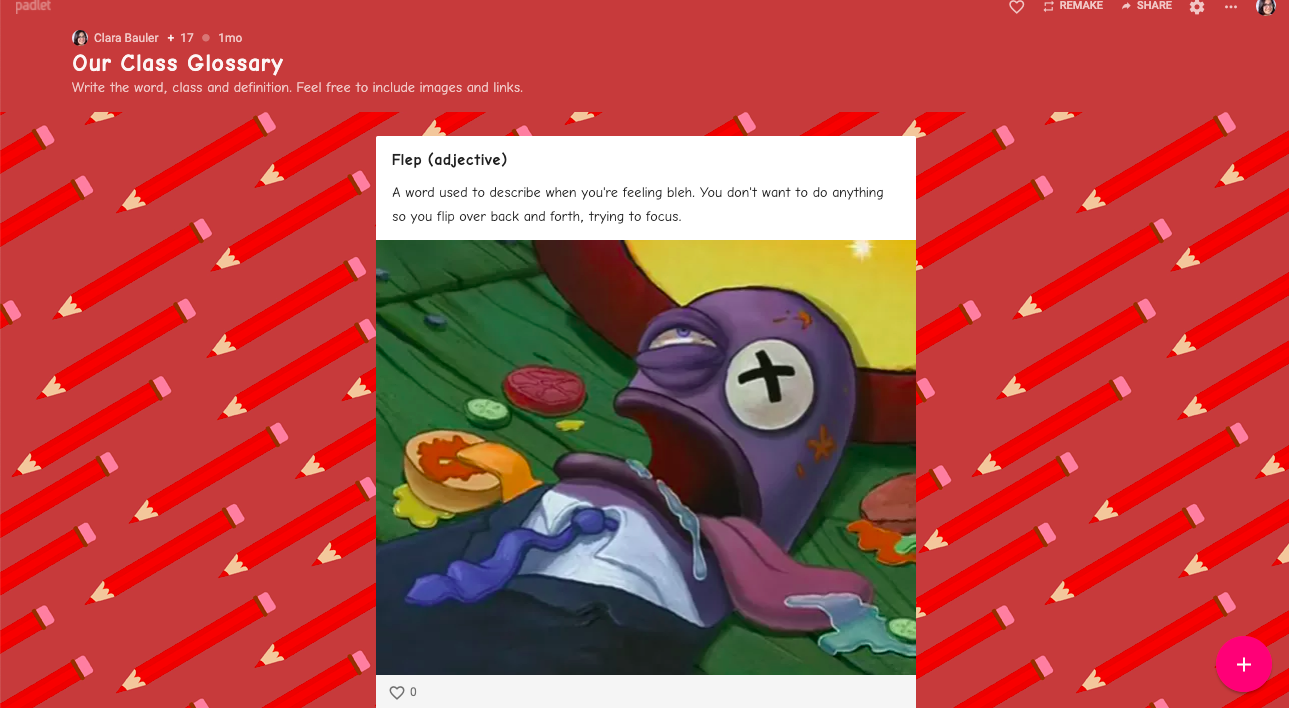

Digital media also helped me foster and support self-expression by allowing students to post images, GIFs, memes, and videos on Padlet. Visuals are widely used for “comprehensible input” or for language receptive tasks. However, there is tremendous power in also using images, drawings and charts for language production. These symbolic tools afford students multiple possibilities to express meaning. Flexibility is key. Below is how we used Padlet to share a create a multimodal class glossary.

Equity and inclusion demand re-examination of our practices. It can be hard to teach with cameras off or to change the ways we organize spaces for education, but allowing multiple entry points to the lesson enabled ALL students to engage. In the face-to-face classroom, students should also have the option of “turning their cameras off.” As teachers, we can focus less on the (often) few students who raise their hands and more on providing a space for EVERYONE to share input, either via writing, drawing or choosing from the many languages students speak. Multilingual learners especially benefit from this rich multimodal environment as they are able to tap into both their linguistic and semiotic resources to engage with varied types of literacy. This flexibility helps in developing reading, writing and vocabulary (Ascenzi-Moreno, Güílamo, & Vogel, 2020). To me, making slides interactive, manipulating and actively using texts, images and symbols to communicate have become indispensable for fostering an equitable and inclusive environment.

A Room for Emotions

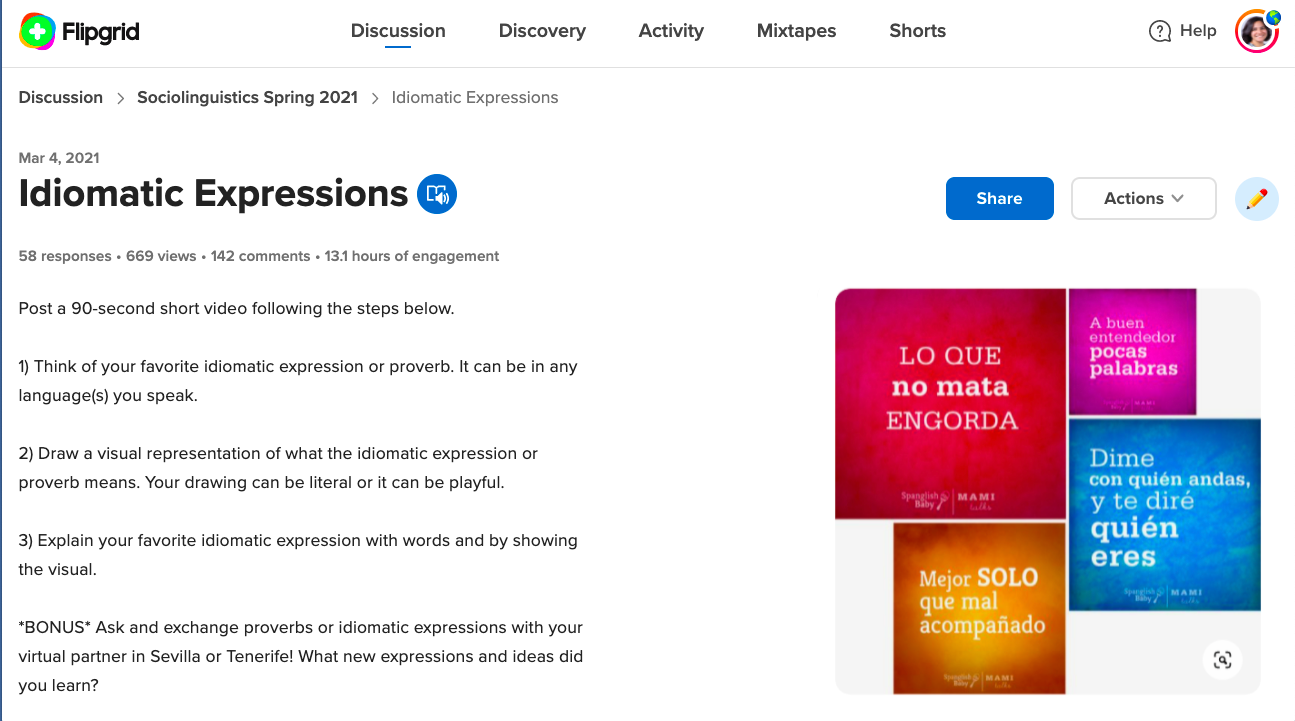

One of the most important things I lost in typical face-to-face teaching practices was the ability to connect and immediately attend to students’ feelings by just approaching students or saying hello. Although dramatically different from physical spaces, the virtual environment also became a place where my students and I could connect. In particular, Flipgrid was very helpful in providing a platform for community building. We shared weekly journals about ourselves, our languages, and our cultural practices. I also used Flipgrid to create a question corner where my students and I could drop videos about anything, from actual questions, to saying hello or provide comments on the topics for the week. When posting on Flipgrid, students could choose to keep cameras on or off. Below is one example of a weekly journal where we shared about our favorite idiomatic expressions.

Asynchronous video platforms such as Flipgrid are perfect for building and sustaining community as they are not bound by a class period time or physical space. Because of that we all had time to share and get to know each other more deeply. I can honestly say that without Flipgrid, I would not have had the opportunity to meet each one of my students as individuals as they shared their stories, expressed their emotions and revealed their personalities every week through short video messages. This is one of the dearest learning moments I had this year. For this reason, Flipgrid will remain my favorite digital tool which I will definitely continue to use in my face-to-face classes.

Mimicking Social Media Conversations

I have always been a huge fan of online discussion boards and it is something I have always integrated with my face-to-face teaching. I even did my whole PhD dissertation on it! During the pandemic, I could experiment with different, more engaging ways, to mimic online discussion boards after social media conversations. I have always wanted to do that because I knew deep down that although great, discussion boards were still considered “assignments” my students needed to “turn in.” I wanted these discussions to feel real and authentic. So, this semester, I started designing online discussion boards very differently. I created routines that would encourage my students to be creative, rely on visuals to make meaning, straying away from the usual “paragraph” format.

The routines involved responding to prompts based on readings and watching videos, as usual, but forced students to craft a more thoughtful post by having them create some sort of visual that would represent their thinking about the texts they were reading and videos they were seeing. We used word clouds, sketches and mind maps to summarize and illustrate our ideas. In addition, the post needed to be short. In some discussions we even experimented with the old 140-character Twitter format. Most importantly, specific prompts for commenting involved responding and reacting based on the visual thinking shared by peers. Below is one example of such discussion where students followed three steps to post and comment. They first took notes using the “I notice, I wonder” format; then they drew relationships and ideas using a physical notebook or google drawing tools. They shared their visual thinking as a screenshot, a very common practice on social media. Finally, they wrote a response to the prompt in Twitter format. The comments were focused on building upon insights, questions, reactions and opinions based on their peers’ sketches.

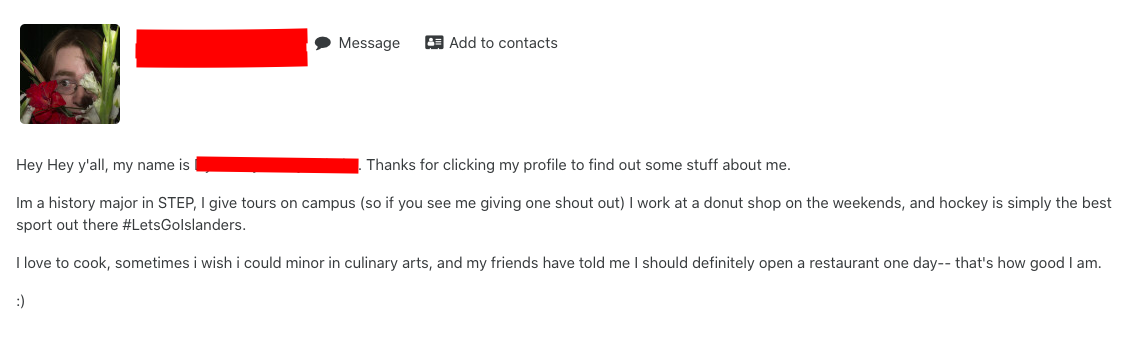

Another advantage of online discussions was the personalization of the messages as we could access students’ profiles as they posted and shared their ideas, just like on social media. Most course management systems, such as Moodle, Google Classroom or Canvas, include a profile option. I often did not pay enough attention to them until the pandemic. The profile option was completely underutilized in my class. But with the need to connect and see each other during the pandemic, creating a profile became an important way students could get to know more about each other. It was also fun because the profile was very visible anytime students posted and looked each other up. Students created a complete Moodle profile that represented who they were. They were asked to include one image (e.g., best selfie, favorite pic or preferred symbol) and three things about themselves (e.g., favorite hobbies, subjects, places, languages you speak or would like to learn, music and food preferences, etc.). Below is an example of a creative student profile.

Promoting democratic conversations requires active engagement in dialogue about controversial issues and divergent opinions. The classroom is often a place where we try to foster these types of conversations via socratic seminars and debates. However, the physical environment and the fast-paced schedule of the typical school day impose real constraints for equitable and inclusive democratic conversations. When we compare classroom discussions with the hot debates and conversations we witness on social media, the limits become even more evident. Online discussion boards have the potential to maximize dialogue as students can post on their own time, affording time to think and craft a careful argument in response to a prompt or a rebuttal from a peer. This discussion can be even more exciting if we employ social media strategies such as the use of shared texts, videos, visuals to enforce the message and a reason to continue the back and forth dialogue. I will continue to refine online discussion boards and use them as the main form of dialogue in my face-to-face classes as they allow for every student to voice their opinions in a personal and meaningful way.

Final Thoughts...

This year, online learning offered me and my students alternatives to often rigid and frequently inequitable schooling practices. If we want to say face-to-face learning is better and there is nothing like having students in school in person, we need to rethink how we organize education spaces no to constrain and limit the kinds of interactions we want to foster. Surprisingly, online environments tend to offer more options for collaboration and participation for all students. This is especially true for many linguistically, culturally and racially diverse students, who can be particularly impacted by the lack of flexibility in a system that was not designed for adaptability and creativity, but conformity. I hope we can build upon important changes and discoveries we made during the pandemic. Let’s not rush to get back to “normal,” but use this opportunity to reimagine how we organize rich spaces for learning, using what works in both physical and virtual environments.

Dr. Clara Vaz Bauler is an associate professor of TESOL/Bilingual Education at Adelphi University, New York. She has a Ph.D. in Education with emphasis in Applied Linguistics and Cultural Perspectives and Comparative Education from UCSB. Clara taught EFL and ESL for thirteen years before becoming a teacher educator. She is passionate about finding and implementing digital media technology to validate and leverage multilingual learners’ linguistic, cultural and racial assets. Dr. Bauler is the co-author of @aumultilingualism podcast with her multilingual freshman college students and is always sharing ideas about language learning and technology on Twitter @Clara Bauler.