And the guest blogs keep coming...

This one is another from Neil Hutchinson, who teaches at Kirkbie Kendal School in the Lake District (on Twitter as @Hutchinsonnet) and here he looks at the foundations of Meanings and Representations when approaching Paper One: Section A.

For students and teachers it can sometimes feel as though the analysis of texts is an arduous uphill struggle. It needn’t be. It’s always heartening to discover you’re not alone on the expedition. The thought that you’re isolated in your decision making is so often the foundation of existential panic. So it was a huge relief to me, and I’m sure countless others, to read this post from fellow guest blogger Mr McVeigh. In this excellent entry, he talks about his approach to Paper One: Section A with a focus on questions 1 and 2. It was heartening to see that there are other practitioners out there making planning a response by examining meaning, before effect, the focus of approaching the questions.

My own approach is broadly similar, with a few differences, and based on the needs of the small bunch of Year 12 students sitting in front of me, sometimes struggling to meet the demands of these questions and scale the heights of the mark scheme, due to shaky foundations beneath their feet.

To remedy this I decided to refine my approach. The historical ‘framework’ approach is of course useful. I do want my students to be able to spot clause elements a mile away. Or label lexical items, with precision, but these alone are not summit markers in a response. Making meanings and representations the top and bottom of their approach, with terminology acting more like the gear to help them along the journey, seems the most sensible route plan.

Mr McVeigh wrote:

I like students to identify at least three representations. I normally say that the author is always represented within a text so that is always a good starting point.

This after he has them, “contextualise the text by identifying the purpose, audience and form of a text (PAF)”.

This is similar to my approach. We spend a lot of time focusing on the layers of representations as a starting point and then allow the meaning to reveal itself as the trek begins. I use the simple image of a triangle (mountain if my extended metaphor has landed thus far), which I will go into in more detail below.

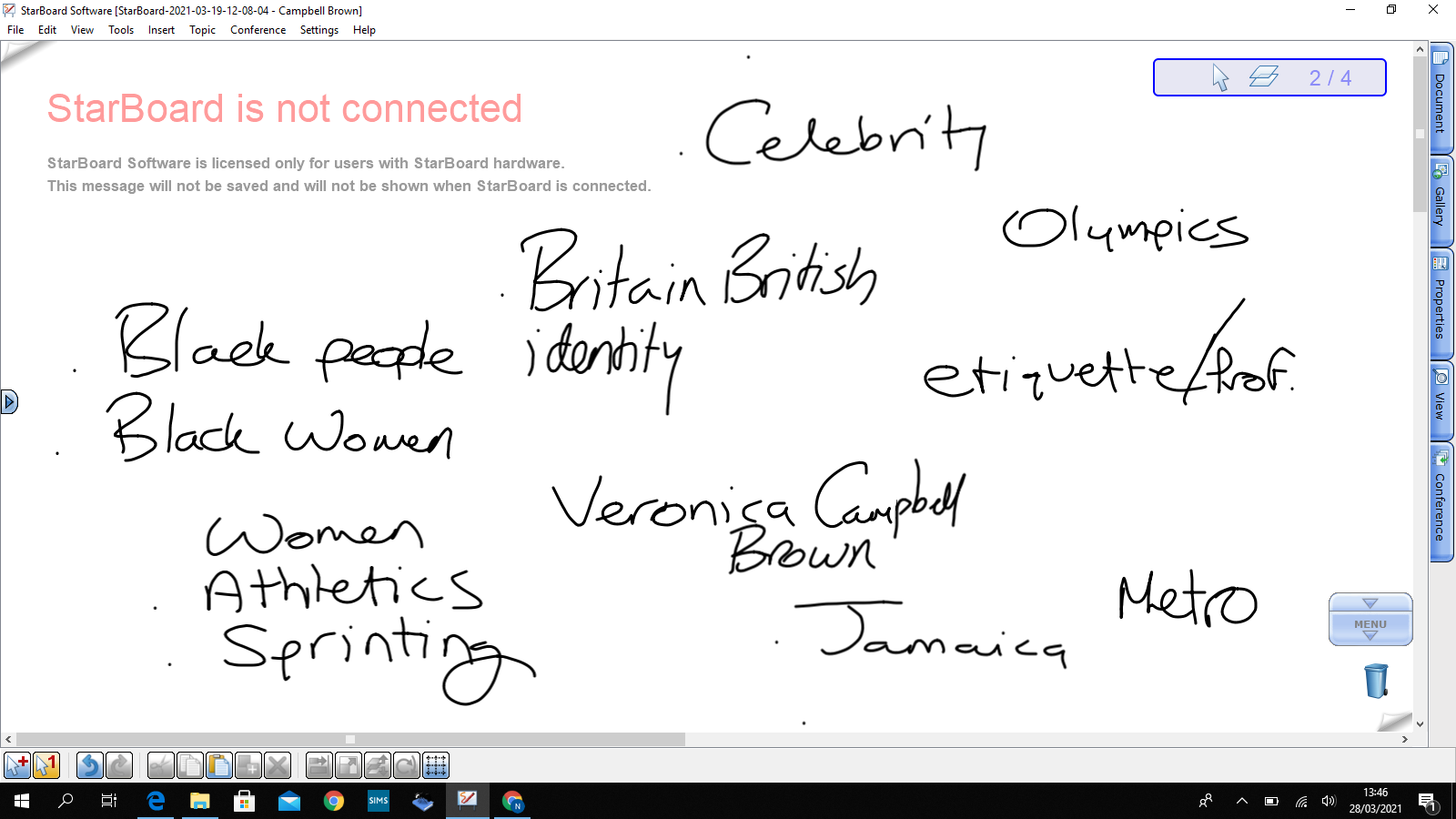

As an example, for upcoming exam(ish) preparation we looked at the June 17 paper, featuring the article from the Metro on athlete Veronica Campbell Brown. Spoiler warning ahead.

The ‘What’

The first thing I asked the students to do was to read the text and simply list all of the representations they can find in the text. I don’t want them to come up with ideas about these representations at this stage. For the students who struggle to generate ideas to discuss in the questions I find this is extremely valuable as it gives them something to aim for. They’re mapping out their route through the questions already before they’ve even thought of anything analytical to say.

At this stage I will write all of these representations on the board:

They listed Veronica Capbell Brown as the most obvious person represented, but from there I encouraged them to consider who else or what else was being represented through her. It stands to reason that people don’t exist in representational vacuums. Especially with celebrities and the world of sport, people see themselves reflected back in those they look up to or hold in high esteem. They were then able to say:

- Women

- Black People

- Black Women

- Jamaica

And just as the students wearing their uniforms outside of school represent our institution I ask them to consider how the individual might represent organisations or institutions. This led to:

- Athletics

- The Olympics

- Sprinting

- Professional Etiquette

- Celebrity

And then through polarisation present in the article, and again similar to Mr McVeigh, they were able to identify:

- Britain/British Identity

- British Athletics

And as Mr McVeigh always reminds them, I ask them to consider how the writer is representing themselves or the publication they’re writing for. So to cap it all off:

- The Metro

- Will Giles (writer)

This really gives the students a solid base camp with a variety of routes to follow. And it is something every student of every ability can do in an exam context. Naturally, those aiming for the highest bands will be more able to discuss the wider implications of the representations on display. They will even be able to spot patterns of wider discourse, which is really going to help them with AO3. More on that later. While those at the lower end will all be able to explore the representation of the individual named in the text, often the most obvious, yet still, the most salient of all listed above.

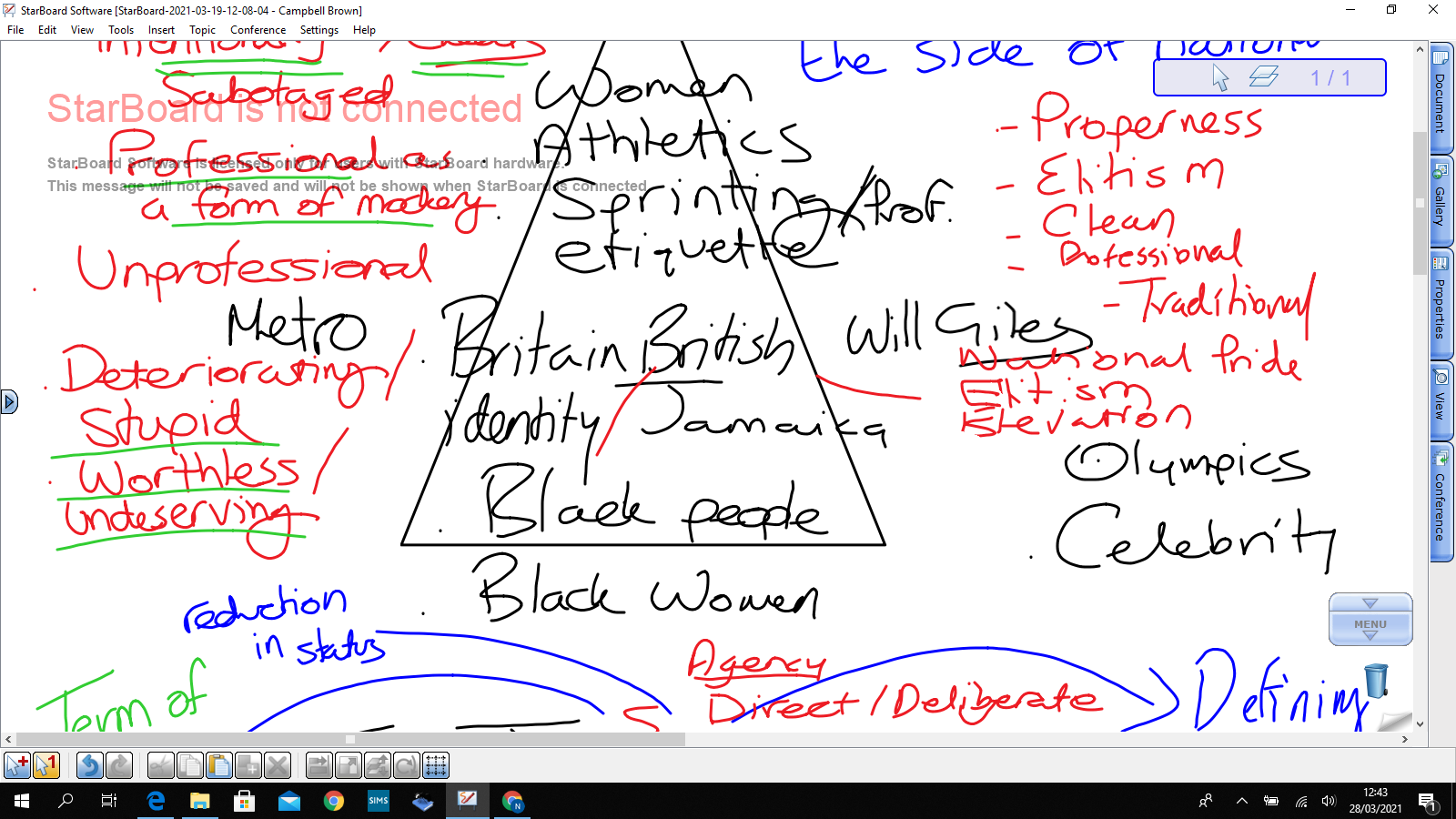

At this point it is worth reminding them that they can’t discuss everything. This is where the interactive whiteboard comes in handy because we now organise that list into a hierarchy (see images below). We decide on this together based on the text in front of us. I ask them is the representation of Veronica Campbell Brown more salient than the representation of black people or women in general? We decide yes. After all she is named in the headline as opposed to say, “Black athlete runs in wrong lane…” or “Female athlete runs in wrong lane…” We do discuss that Campbell Brown is referred to as “The Jamaican” but we consider this as part of the patriotic, tribal stance The Metro is adopting, which we discuss later.

Before developing that, I first ask them if this seems more openly critical of black people or of women? For simplicity, does it seem more racist or sexist? That is not to say it is neither, arguably these prejudices exist between the lines because they feed into the wider social discourses, which are still present in our society. What we are doing at this stage is glancing back over the whole text and spotting what jumps out, again before we have really started to think of the ‘How’. They decide that for a number of reasons, the representation of women seems salient. They look to the overall discourse structure of listing Campbell Brown’s achievements in the opening and then following it with the angry sounding second paragraph, in which Giles utilises the verb phrase, “managed to RUN…” They felt this fed into a wider social discourse of belittling successful women’s achievements.

The final order is listed above in the images of my board. The triangle/mountain image comes into its own here because although Veronica Campbell Brown is undoubtedly the peak in terms of representation, that can only exist on the foundation of typical/historical representations that exist within society. Her image in this article rests on the patterns of how women, black people, athletics etc are represented in our wider culture.

Before moving on to discussing how these representations were being established through language, I emphasised with students that once they had organised them in order of salience they could choose any three to focus on in their answer. Again this is crucial in eliciting a response from every student which is personal and potentially different. The lower ability students may want to focus on the top three whereas those aiming for the highest marks may want to start at the top and pull in something less obvious and perhaps more perceptive.

The ‘How’

As this article is more about an approach to the questions, I will focus less on this part. But it is here where we start to come up with statements about how these people and institutions are being represented. Again, nothing too linguistic at this stage. Simply what seems to be jumping out? These can be seen in red in the image, but they decided VCB was being represented negatively as either a heartless cheat or as an incompetent woman who did not seem deserving of her accolades. As mentioned above it was very easy for them to now suggest that women are often ridiculed in our wider culture as a way to downplay their achievements. Some discussed, away from the world of sport, the ongoing, relentless and hateful treatment of Mary Beard here.

It is only now we get to frameworks. Once they have organised their thinking in this way, the language and structure seems to reveal itself in a way it otherwise wouldn’t have done before. They have a solid route and the terrain looks easier for them to negotiate. If you want a more detailed approach for this stage, I recommend this one.

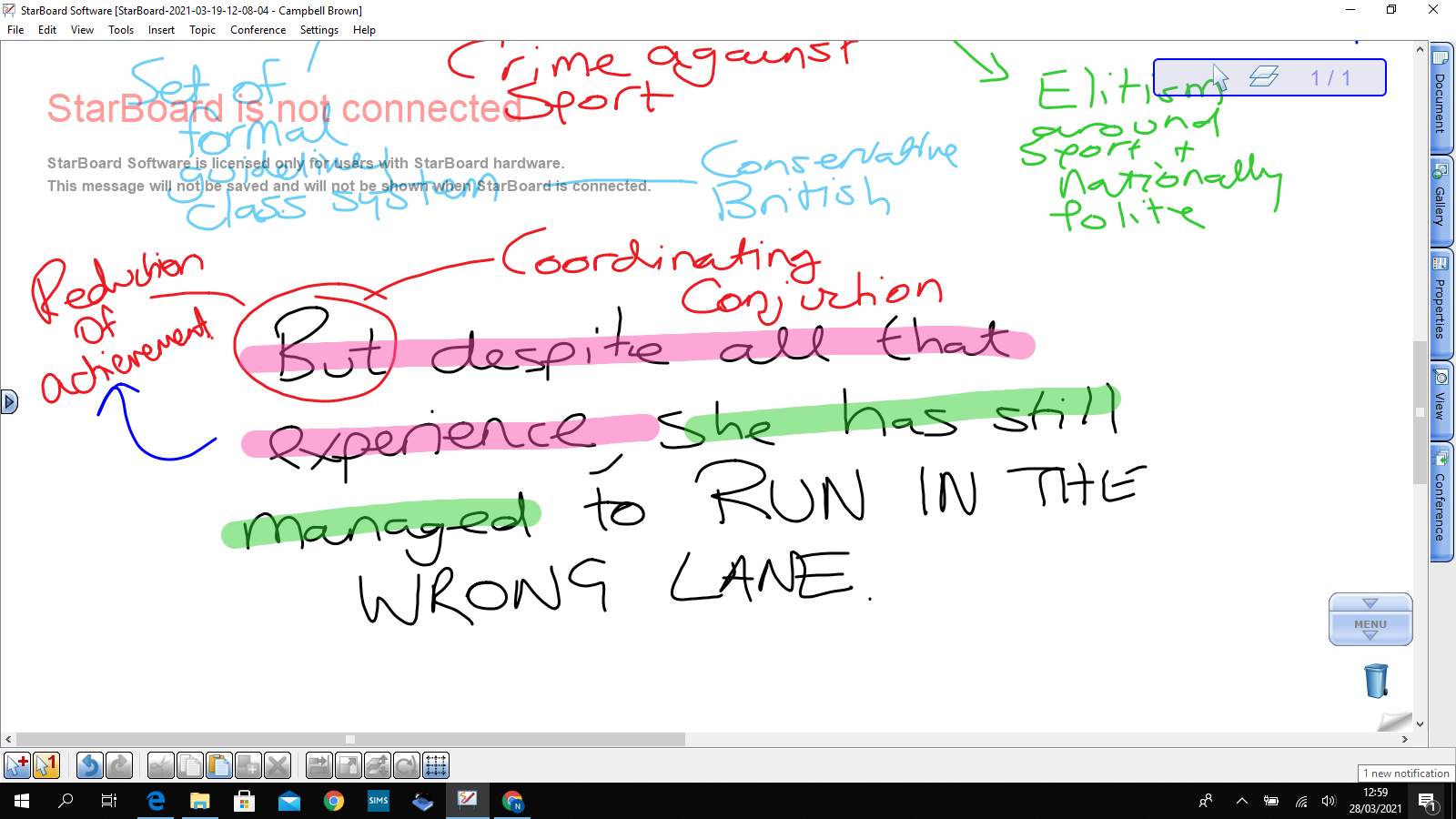

With these representations and meanings in mind we explored that second paragraph in more detail:

But despite all that experience, she has still managed to run in the wrong lane.

Verb phrase aside, they discussed the sentence opening with the coordinating conjunction functioning as the opening of the adverbial, something I’m sure would have led to much prescriptivist moaning, if they happened upon the Metro that morning on their commute. Why make this deliberate “error”? Well it must be to emphasise that what follows is bigger than all of those achievements just listed. This ramps up the tone of anger, sarcasm, humour and does a great job of reducing this successful athlete to the status of either ‘silly girl’ or ‘evil witch’ or both. We re-wrote this sentence in a variety of ways and decided the fronted adverbial was loaded with meaning, which supported what they had already said about the representations. Then there’s the obvious graphology of the capitalisation to anchor this.

The ‘Why’

If in reading this so far you have wondered where the PAF (purpose/audience/form) or GCAP (genre/context/audience/purpose) as I teach, comes in. Well it’s here. I call these the macro concepts of linguistic analysis. The micro elements come from the areas of the frameworks or language levels and should always be used to comment on the macro concepts.

We now make decisions about these macro concepts and the impact they have had in the writing of the text. Did Will Giles set out to destroy this athlete because she is a woman or is this an unfortunate consequence of something else from GCAP? Starting with the macro concept of Context of production, we looked at the date (2015), and the patterns of language which seemed to focus on British athletics and came up with the idea that there may have been a renewed interest in the sport in this country as a result of the 2012 Olympics. This focus on nationalism and tribal loyalties to Team GB goes some way to underpinning what The Metro might have been trying to do in this article through these representations. They have perhaps tried to position us against this Jamaican athlete to drum up tribal support for our team, but have used conventional negative representations of women to do it. We also discussed the impact of The Metro and its tabloid style in the informal register adopted in our example. On the part of the producer, it may only be a funny (not funny) story for someone to read in 5 mins on the bus (Audience+context), but as we know, context of reception is everything and for a young woman aspiring to be an athlete this could have a far reaching impact.

This layering of meaning according to GCAP is going to unlock a variety of interpretations of features and patterns that will allow the students to score highly in AO3. As with subject terminology for AO1, points about genre, context, audience and purpose are only as valuable as the argument you pin them to.

So just because we come to the macro concepts of GCAP last in this strategy does not make it an afterthought. Quite the opposite in fact. An understanding of the construction of a given text from the perspective of GCAP is part of the foundation to understanding the representations in the first place. But rather than taking the approach of, ‘this is a tabloid newspaper article therefore it will represent x as y’, I much prefer, ‘x is represented as y, possibly because this is a tabloid newspaper article but it may be more to do with z.’

I think that the macro concepts should be something outlined and discussed in introductions as part of the foundation on which the students can build. As long as they’re tied to meanings and representations and contribute to the direction of travel. So putting all of the above together a successful intro to a Question 1, with this text as a basis, may look like:

In Text A, The Metro and writer Will Giles, offer a stereotypically negative representation of women, through Veronica Campbell Brown, as a means of generating national support for British Athletics in the wake of the 2012 Olympics. At various points Campbell Brown is represented as foolish and dull-witted, someone undeserving of her previous achievements and at worst, a dishonest cheat. Giles adopts a classically tabloid style to create these meanings, potentially for click-bait in an online format or to entertain a tribal sports fan on their daily commute.

This is slightly wordy, but you get the picture. This intro condenses everything into one paragraph, which covers three strands of representation and their link to audience, genre and two contextual factors.

Hopefully this has given you some ideas about how to approach the Paper One mountain with students, particularly mixed ability students. Well done for reaching the summit!