There's a good article by Matthew Engel on the BBC News magazine this week which takes a look at the UK's attitudes to American language imports.

He tells us at the beginning that "The Americans imported English wholesale, forged it to meet their own

needs, then exported their own words back across the Atlantic to be

incorporated in the way we speak over here" which is a model that is fairly well-established in existing writing about American English, but one that comes with a few problems attached.

In one sense it still presumes that English English (or British English) is the standard to which all other varieties aspire and that while the Americans have been busy forging away (possibly a loaded metaphor, suggesting that they're making an inferior copy rather than bashing it with lump hammers and making it new) our language remains unchanged, aloof and just better, dammit. And what do we mean by "our" language anyway?

The title of the article is intriguing, because it suggests - as Lynne Murphy has identified in her tweets about this piece - that Americans aren't people, or at least they're not the "people" to whom Engels was addressing his piece. It's a strange piece of audience positioning for an author who must know that the BBC site is read all across the world... even by Americans. It smacks a bit of marking out territory and dividing lines between languages...which is OK, if that's what floats your Mayflower.

Also, towards the end when he makes a point about enjoying the "vigour and vivacity" of American English (words that always get used, often along with "articulate" when describing a language, or speaker of a language, that you think is good at "keeping it real" but probably not as clever as you) Engels states "...what I hate is the sloppy loss of our own distinctive phraseology

through sheer idleness, lack of self-awareness and our attitude of

cultural cringe. We encourage the diversity offered by Welsh and Gaelic -

even Cornish is making a comeback. But we are letting British English

wither". This strikes a fairly prescriptivist note, and suggests that as we import American words our home-grown variety dies out. Is it really like that?

I know that I cringe when I hear UK teenagers talk about the feds rather than the old bill, filth or boy dem (all good, old-fashioned British names for the police) but does that mean that the US word has taken the place of an English word, or just that its temporarily occupying its place while fashions come and go?

In one way, Engels is right that American words are creeping in through popular culture and spreading throughout British society, but in other ways he's not: regional varieties of English are apparently growing in strength, with some dialect terms making a comeback. While the bigger picture might be of a drift towards more Americanisms, it's not all one-way traffic and the drift is not uniform.

The article - despite my misgiving here - is certainly worth a read for anyone looking at global Englishes and the spread of American English around the world, as well as those looking for a good topic for a future Language Discourses question on ENGA3.

You can find a lot more about American English (and British English too!) on Lynne Murphy's excellent blog Separated by a Common Language and by following her on Twitter.

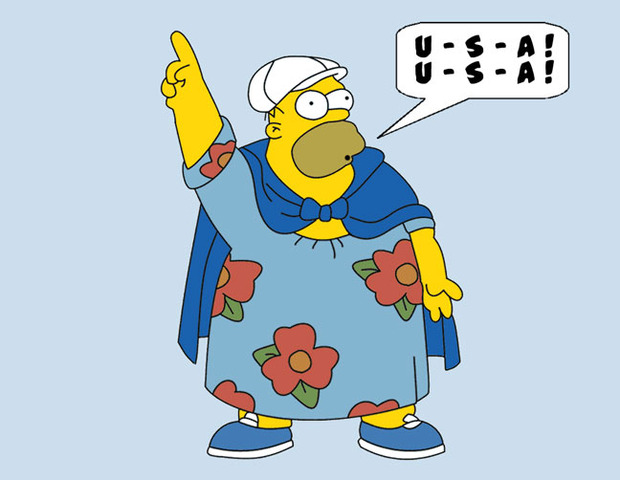

Edited and republished 13.07.11 because I've struggled to distinguish between save and publish on Blogger's new interface. D'oh! No, I mean "dash it!"

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Follow EngLangBlog on Bluesky

The old Twitter account has been deleted (because of both the ennazification and enshittification of that site) so is now running on Bluesk...

-

As part of the Original Writing section of the NEA, students will be required to produce a commentary on their piece. This blog post will pr...

-

As lots of students are embarking on the Language Investigation part of the Non-Exam Assessment, I thought it might be handy to pick up a fe...

-

When Dan asked what he should post about next on this blog, one of the most common responses was this, the World Englishes topic. Maybe ...