Sunday, December 18, 2011

Language Police

Just a quick link to a good piece in yesterday's Guardian Weekend by Oliver Burkeman about attitudes to language mistakes, grammatical errors and other abuses.

Thursday, December 15, 2011

Unfriended for grammar fails

There's a good article here on ZDNet by Charlie Osborne about grammar, spelling and punctuation on social networking sites. She takes a look at how technology has been blamed for grammar failures, but how the fault might lie with how we teach English in schools.

While it's clearly important to teach grammar as part of secondary English, the problem lies in how we teach it. If it's just a dry naming of parts with little sense of what the effects of grammar choices are then we're probably doomed to the nightmare back to the future scenario that Simon Heffer (and his chum, Michael Gove) longs for.

One problem is that many of the gripes about grammar that are often brought up are either matters of taste, rather than "rules" which affect how we actually understand one another, so one person's error is another person's normal usage. That's not to excuse basic errors like you're/your, their/there (which bug me, even though I'm what Heffer would probably call a trendy-lefty linguist).

One explanation for such errors is that in a time of much higher basic literacy rates than ever before, we're seeing more and more people using forms of communication like Facebook, Twitter and texting than we would ever have known before, and while basic literacy is higher, not everyone is as highly educated as those who wrote for public consumption in the past.

So while the footballer, Joey Barton tweets about his interest in Noam Chomsky and Euroscepticism to about one million followers, you'd have needed decades of formal education and a university degree to communicate with that many people in 1870 or 1950.

Not surprising really, because a footballer like Joey Barton generally talks with an educated right foot (and in Barton's case, the occasional headbutt) rather than an educated lexicon. And as a follower of Barton on Twitter and admirer of his genuine interest in exploring the world of knowledge - not something footballers are well known for - I don't mean to criticise or patronise him in any way, but when you look at the history of language, working class men like Barton have rarely had such a public platform for their words.

It's an argument that also links with Joshua Foer's piece in the New York Times in which he looks at how our reading habits have changed from "intensive" knowledge of a limited range of books to "extensive" reading of many texts, including books, newspapers and text messages. And as more and more people write and text in English around the world, perhaps the centrifugal force that has previously bound English usage to the core values of Standard English begins to lose its power, with more and more mis-spellings and grammatical errors circulating, growing in influence and perhaps changing the language beyond recognition. A doomsday scenario for Standard English, or the natural evolution of a growing language?

While it's clearly important to teach grammar as part of secondary English, the problem lies in how we teach it. If it's just a dry naming of parts with little sense of what the effects of grammar choices are then we're probably doomed to the nightmare back to the future scenario that Simon Heffer (and his chum, Michael Gove) longs for.

One problem is that many of the gripes about grammar that are often brought up are either matters of taste, rather than "rules" which affect how we actually understand one another, so one person's error is another person's normal usage. That's not to excuse basic errors like you're/your, their/there (which bug me, even though I'm what Heffer would probably call a trendy-lefty linguist).

One explanation for such errors is that in a time of much higher basic literacy rates than ever before, we're seeing more and more people using forms of communication like Facebook, Twitter and texting than we would ever have known before, and while basic literacy is higher, not everyone is as highly educated as those who wrote for public consumption in the past.

So while the footballer, Joey Barton tweets about his interest in Noam Chomsky and Euroscepticism to about one million followers, you'd have needed decades of formal education and a university degree to communicate with that many people in 1870 or 1950.

Not surprising really, because a footballer like Joey Barton generally talks with an educated right foot (and in Barton's case, the occasional headbutt) rather than an educated lexicon. And as a follower of Barton on Twitter and admirer of his genuine interest in exploring the world of knowledge - not something footballers are well known for - I don't mean to criticise or patronise him in any way, but when you look at the history of language, working class men like Barton have rarely had such a public platform for their words.

It's an argument that also links with Joshua Foer's piece in the New York Times in which he looks at how our reading habits have changed from "intensive" knowledge of a limited range of books to "extensive" reading of many texts, including books, newspapers and text messages. And as more and more people write and text in English around the world, perhaps the centrifugal force that has previously bound English usage to the core values of Standard English begins to lose its power, with more and more mis-spellings and grammatical errors circulating, growing in influence and perhaps changing the language beyond recognition. A doomsday scenario for Standard English, or the natural evolution of a growing language?

Thursday, December 08, 2011

Small words that mean a lot

When we talk about controversial words on this blog, most of

them are “big words”: ones loaded with connotations and steeped in contentious

history, such as the dreaded n-word, housewife, slut

and mong. Fair enough, they can often be very controversial. But little words

are also important and a couple of those little words – so and thank you – have

come in for a bit of analysis of late.

Last week, Radio 4 took a look at how so is increasingly

being used as a discourse marker. It’s also been looked at here and here.

According to some suggestions, so is making the move from webpage to spoken

discourse in the kind of text to talk style that has given us LOL and OMG as

everyday spoken expressions.

Elsewhere, the changing face of British politeness was beingexplored by the Daily Mail, which – as you might imagine – saw a future of doom

and rudeness (not to mention nasty illegal immigrants, sponging single mums and

Americans) in the changing place of thank you in our popular politeness

lexicon.

The Daily Mail story wasn’t entirely new, as it was covered

by The Daily Telegraph the year before, that time with a slightly different

(but still rather spurious) “survey” into changing habits.

Thursday, December 01, 2011

emagazine English Language conference 2012

The second emagazine English Language conference is now taking bookings and promises to be another really excellent event. We've booked a great line-up, with talks by David Crystal, Angela Goddard, Marcello Giovanelli and the head of Aston University's Centre for Forensic Linguistics, Tim Grant.

The conference blog is here and you can find out more about what we're putting on here on the English and Media Centre's conference page. Also, details of last year's fantastic conference can be found here if you're interested.

The conference blog is here and you can find out more about what we're putting on here on the English and Media Centre's conference page. Also, details of last year's fantastic conference can be found here if you're interested.

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

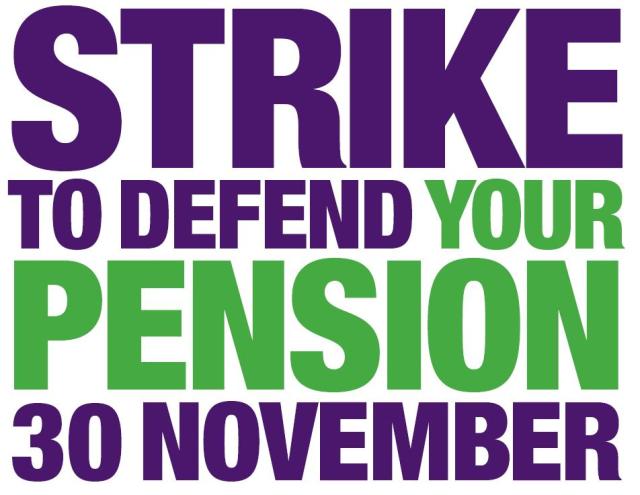

On strike

This blog is officially on strike today in solidarity with striking public sector workers.

Do not cross the picket line by posting comments!

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Big and clever, but not insulting

Swearing is bad, right? We're always told it's not big or clever to swear, but I can't be the only person to find a well-chosen swearword hilariously funny.

Swearing has had a long and rich history in English, partly because of the changing social attitudes we've had to certain taboo terms and the ways in which swear words often reflect a changing world. Mark Lawson in today's Guardian* offers a look at this in the light of recent media worries over Strictly Come Dancing and the X Factor, but he raises other points about the history of swearing too.

Many words have, he points out with the help of Language God, David Crystal, changed from perfectly innocent usage to taboo terms over time (the c-word - the one that isn't Cameron - being a good example of this) but others have gone the other way and lessened in their impact (sod and bugger, for instance).

And it's changing social attitudes that are of interest to the High Court judge, Mister Justice Bean who has rules that police officers being told to "f**k off" are hardly likely to be insulted because they're so used to it, it's water of a f**k's back, sorry, duck's back.

This doesn't appeal to Janet Daley in the Daily Telegraph who sees swearing as a form of abuse and disrespect that our public servants shouldn't be subjected to. For her it's the tip of the iceberg: today swearing tomorrow anarchy. And it's an argument that Mark Lawson alludes to in his piece as well. If swearing is so widespread that it's no longer insulting, or so ubiquitous that we don't even know we're doing it, what value does it actually have?

We've covered swearing on this blog many times previously, so just click on the label to see all the relevant posts about it.

* thanks to Jon D for the link

edited on 24.11.11 to add:

My legal adviser (the Mrs) tells me that the issue over Mister Justice Bean's pronouncement is not really that new and is less connected to "insult" than it is to the "alarm, harassment and distress" in the wording of public order charges.

She tells me that there is a big difference between swearing and swearing at someone in the eyes of the law, so if a suspect were to say "I've never seen that f**king flatscreen!", that would not generally considered to be something that would cause distress to an arresting officer (or imaginary bystander), while "F**k off you idiot; I've never seen that flatscreen before" might be perceived as causing distress as it is directed towards the officer.

This makes an interesting distinction between swearing in general and swearing at someone.

Swearing has had a long and rich history in English, partly because of the changing social attitudes we've had to certain taboo terms and the ways in which swear words often reflect a changing world. Mark Lawson in today's Guardian* offers a look at this in the light of recent media worries over Strictly Come Dancing and the X Factor, but he raises other points about the history of swearing too.

Many words have, he points out with the help of Language God, David Crystal, changed from perfectly innocent usage to taboo terms over time (the c-word - the one that isn't Cameron - being a good example of this) but others have gone the other way and lessened in their impact (sod and bugger, for instance).

And it's changing social attitudes that are of interest to the High Court judge, Mister Justice Bean who has rules that police officers being told to "f**k off" are hardly likely to be insulted because they're so used to it, it's water of a f**k's back, sorry, duck's back.

This doesn't appeal to Janet Daley in the Daily Telegraph who sees swearing as a form of abuse and disrespect that our public servants shouldn't be subjected to. For her it's the tip of the iceberg: today swearing tomorrow anarchy. And it's an argument that Mark Lawson alludes to in his piece as well. If swearing is so widespread that it's no longer insulting, or so ubiquitous that we don't even know we're doing it, what value does it actually have?

We've covered swearing on this blog many times previously, so just click on the label to see all the relevant posts about it.

* thanks to Jon D for the link

edited on 24.11.11 to add:

My legal adviser (the Mrs) tells me that the issue over Mister Justice Bean's pronouncement is not really that new and is less connected to "insult" than it is to the "alarm, harassment and distress" in the wording of public order charges.

She tells me that there is a big difference between swearing and swearing at someone in the eyes of the law, so if a suspect were to say "I've never seen that f**king flatscreen!", that would not generally considered to be something that would cause distress to an arresting officer (or imaginary bystander), while "F**k off you idiot; I've never seen that flatscreen before" might be perceived as causing distress as it is directed towards the officer.

This makes an interesting distinction between swearing in general and swearing at someone.

Technology and language change

There's an good article from Natasha Lomas of Silicon.com here which takes a look at how technology has influenced recent language change. It includes contributions from God of language, David Crystal and the OED's John Simpson, so it's got proper linguistics stuff there, plus it gives us some good techy insight into different fields such as text messaging, social networking and Lolcats.

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Tweet to speech

Ben Trawick-Smith's Dialect Blog has got a good range of posts on it about spoken language, often material on accents and dialects, but here he looks at how online language abbreviations such as OMG, LOL and WTF have worked their way into some people's spoken language.

We've had a look at this phenomenon on this blog before, here in a piece by Emma Bertouche on hashtag creeping into spoken forms, and here back in February this year.

We've had a look at this phenomenon on this blog before, here in a piece by Emma Bertouche on hashtag creeping into spoken forms, and here back in February this year.

Discussing disgusting

There's a good piece here on the BBC News magazine site about the word disgust and its changing meanings and usage in English. As well as being a good case study of semantic change, it offers an interesting angle on how new analytical methods can be used to track language change, in this case Google n-grams and digital corpus searches.

Convergence in action in Australia

There's a neat example here of how accommodation theory can work. When Barack Obama visited Australia he used a few Australianisms to help strike up a rapport with prime minister, Julia Gillard.

Accommodation theory, as theorised by Howard Giles, consists of convergence and divergence, the former involving speakers moving closer to each other in speech style (for example, a teacher downwardly converging with a younger student to speak more on their level), the latter showing the opposite (for example, a speaker deliberately altering their speech style to be more noticeably different from those around her).

Accommodation theory, as theorised by Howard Giles, consists of convergence and divergence, the former involving speakers moving closer to each other in speech style (for example, a teacher downwardly converging with a younger student to speak more on their level), the latter showing the opposite (for example, a speaker deliberately altering their speech style to be more noticeably different from those around her).

Friday, November 04, 2011

English for the English; Englishes for the rest?

Does England have any control of what is called "English" or will, as one Telegraph reader wittily claims, "The English ... have as much control over English as the Italians have

over pizza and Indians over chicken korma"?

It might seem like a strange question, given that the general consensus is that English (the language) derives from England (the nation), but it's one that is increasingly being asked as new varieties of English spring up all over the world, each with its own distinct character and linguistic identity.

We've already seen that many English speakers get very worked up about "their" language being taken over by Americanisms, but what about when their language is picked up by Malaysians, Indians, Nigerians, and Chinese? For many, these varieties of English are judged as inferior, broken, stripped down and poorly learnt versions of the original and best form, but that's a view that was never popular among linguists and has been the subject of some fairly strongly-worded arguments in English teaching circles over the last twenty or so years.

For a long time, this neo-colonialist view - that a world English (singular) should be taught and that English English was the gold standard - seemed to be the mindset of many English educators (and perhaps their students too) where the focus was very much on teaching Johnny Foreigner the right sort of English.

But then came along Braj Kachru with his circle model of World Englishes (Note the plural!):

The model has the "traditional bases" of English at its centre - the inner circle - and then widens to include countries in the outer circle where English has had an historical or political role, before moving into the expanding circle where English is generally used as a "lingua franca", a language of convenience to communicate between people who do not have English as their first language.

The model is not without its critics though, and some have argued that it neglects the "norms" of English and lets the Englishes at the fringes drift too far away from the core linguistic values of a standard Global English. In fact, Kachru debated this with Randolph (now Lord) Quirk (founder of the Survey of English Usage at UCL, where I work, so I must be careful what I say!).

From the other side of the linguistic divide, the model has been criticised for not being radical enough. It still places England and the USA at its heart and therefore creates the impression that the English language of the expanding circle orbits around them, that England is still at the centre of the universe.

Now, while Jeremy Clarkson and most of the Conservative Party would probably agree with that notion, sitting in the snug bar of a Tunbridge Wells gentleman's club and polishing their miniature soldier figurines, it's hard to see how England can really claim any ownership over the Englishes spoken beyond its own borders. Even within those borders the language is in a state of constant flux and has a rich history of regional, social and ethnic variation, and that's before you even set foot on an ocean liner to cross the Atlantic or a prison ship to reach Australia.

The most recent debate has been over just this issue, with Dr. Mario Saraceni, a linguist from Portsmouth University, arguing in the September 2011 edition of Changing English (as reported here) that it's time to get away from the mindset that English is "spreading" and that "the psychological umbilical chord linking English in the world to its arbitrarily identified spatio-temporal and cultural centre be decidedly and conclusively severed". It's a bit of a mouthful, as you can see, but he's essentially calling for a clean break to be made between England and English.

To support his case, he quotes Henry Widdowson who said "How English develops in the world is no business whatever of native speakers in England, or the United States, or anywhere else. They have no say in the matter, no right to intervene or pass judgement. They are irrelevant."

In the interview below, Saraceni talks about a student of his, from Malaysia who says he feels like English is a "borrowed language", an idea that Saraceni develops in his paper, arguing that "Language is intimately connected to one's intellect and one's perception of Self and the idea of using a borrowed language, especially when this language is one's main language, has significant implications for the way one sees him/herself in relation to those considered to be the legitimate owners of that language".

In a sense (and I hope I'm getting this right) we shouldn't really be talking about anyone owning the language, that we should grow up and be less sentimental about what is essentially a tool for billions of people.

That's all well and good, but we know from previous language debates that arguments over language are rarely contained to the words, the sounds and the grammar of a language, but are much more often about our views of other people, their habits, their cultures and our own prejudices. So, in that context and to many linguistic nationalists on the comment pages of the Mail or the opinion pages of the Telegraph, what Saraceni says here is incendiary stuff.

Dr Mario Saraceni from University of Portsmouth on Vimeo.

(source: http://www.physorg.com/news/2011-11-queen-english.html)

It might seem like a strange question, given that the general consensus is that English (the language) derives from England (the nation), but it's one that is increasingly being asked as new varieties of English spring up all over the world, each with its own distinct character and linguistic identity.

We've already seen that many English speakers get very worked up about "their" language being taken over by Americanisms, but what about when their language is picked up by Malaysians, Indians, Nigerians, and Chinese? For many, these varieties of English are judged as inferior, broken, stripped down and poorly learnt versions of the original and best form, but that's a view that was never popular among linguists and has been the subject of some fairly strongly-worded arguments in English teaching circles over the last twenty or so years.

For a long time, this neo-colonialist view - that a world English (singular) should be taught and that English English was the gold standard - seemed to be the mindset of many English educators (and perhaps their students too) where the focus was very much on teaching Johnny Foreigner the right sort of English.

But then came along Braj Kachru with his circle model of World Englishes (Note the plural!):

|

| from http://metee-translation.blogspot.com/2010/06/you-are-now-officially-welcomed-to.html |

The model is not without its critics though, and some have argued that it neglects the "norms" of English and lets the Englishes at the fringes drift too far away from the core linguistic values of a standard Global English. In fact, Kachru debated this with Randolph (now Lord) Quirk (founder of the Survey of English Usage at UCL, where I work, so I must be careful what I say!).

From the other side of the linguistic divide, the model has been criticised for not being radical enough. It still places England and the USA at its heart and therefore creates the impression that the English language of the expanding circle orbits around them, that England is still at the centre of the universe.

Now, while Jeremy Clarkson and most of the Conservative Party would probably agree with that notion, sitting in the snug bar of a Tunbridge Wells gentleman's club and polishing their miniature soldier figurines, it's hard to see how England can really claim any ownership over the Englishes spoken beyond its own borders. Even within those borders the language is in a state of constant flux and has a rich history of regional, social and ethnic variation, and that's before you even set foot on an ocean liner to cross the Atlantic or a prison ship to reach Australia.

The most recent debate has been over just this issue, with Dr. Mario Saraceni, a linguist from Portsmouth University, arguing in the September 2011 edition of Changing English (as reported here) that it's time to get away from the mindset that English is "spreading" and that "the psychological umbilical chord linking English in the world to its arbitrarily identified spatio-temporal and cultural centre be decidedly and conclusively severed". It's a bit of a mouthful, as you can see, but he's essentially calling for a clean break to be made between England and English.

To support his case, he quotes Henry Widdowson who said "How English develops in the world is no business whatever of native speakers in England, or the United States, or anywhere else. They have no say in the matter, no right to intervene or pass judgement. They are irrelevant."

In the interview below, Saraceni talks about a student of his, from Malaysia who says he feels like English is a "borrowed language", an idea that Saraceni develops in his paper, arguing that "Language is intimately connected to one's intellect and one's perception of Self and the idea of using a borrowed language, especially when this language is one's main language, has significant implications for the way one sees him/herself in relation to those considered to be the legitimate owners of that language".

In a sense (and I hope I'm getting this right) we shouldn't really be talking about anyone owning the language, that we should grow up and be less sentimental about what is essentially a tool for billions of people.

That's all well and good, but we know from previous language debates that arguments over language are rarely contained to the words, the sounds and the grammar of a language, but are much more often about our views of other people, their habits, their cultures and our own prejudices. So, in that context and to many linguistic nationalists on the comment pages of the Mail or the opinion pages of the Telegraph, what Saraceni says here is incendiary stuff.

Dr Mario Saraceni from University of Portsmouth on Vimeo.

(source: http://www.physorg.com/news/2011-11-queen-english.html)

Monday, October 31, 2011

Twitterology

|

| don't kill the spares |

Thursday, October 27, 2011

"Twitter generation loses love of lexis"

...or so this story in today's Daily Mail would have you believe. According to the article, words like cripes, shenanigans and cad are

all dying out because younger generations simply don't know what they

bally mean (And it's perhaps not just the fault of the younger

generation but technology as well because my spell-checker has just

red-lined both cripes and bally.).

The story seems to be linked to the publication of a survey for the book Planet Word (presumably a tie-in to Stephen Fry's BBC series of the same name) and to be fair, the expert they quote, the author of the book JP Davidson, doesn't bemoan the alleged decline, but has this to say:

This sounds like good sense and isn't in any way as prescriptive as the rest of the Mail's tone (managing of course to tie in some aspect of British identity being eroded as it always does), but the comments from Mail readers start to pour scorn on such descriptive views, arguing (among other things) that the once proud language of Shakespeare is now degenerating into a series of txt-grunts (a kind of Crumbling Castle model for the text generation) and that young people are doing it because they "are even allowed to use text speech in exams now", conveniently (or stupidly) misunderstanding the difference between studying and using. D'oh!

But, there is an interesting argument to be had here over the potentially limiting effects of technology on our lexicon - both individual and shared - because as this new app demonstrates, predictive texting has evolved to offer us predictive messaging.

Ultimately,

will this lead us into a reduced set of lexical and grammatical

choices, fulfilling the Mail's to hell in a handcart predictions in the

article above?

The story seems to be linked to the publication of a survey for the book Planet Word (presumably a tie-in to Stephen Fry's BBC series of the same name) and to be fair, the expert they quote, the author of the book JP Davidson, doesn't bemoan the alleged decline, but has this to say:

This could be viewed as regrettable, as there are some great descriptive words that are being lost and these words would make our everyday language much more colourful and fun if we were to use them.

'But it's only natural that with people trying to fit as much information in 140 characters that words are getting shortened and are even becoming redundant as a result.

'The folly is to try and stem the tide of the new whether they emerge from rap, technology, teenspeak, or the multitude of jargons that we invent to make shortcuts and communication more efficient between groups.

This sounds like good sense and isn't in any way as prescriptive as the rest of the Mail's tone (managing of course to tie in some aspect of British identity being eroded as it always does), but the comments from Mail readers start to pour scorn on such descriptive views, arguing (among other things) that the once proud language of Shakespeare is now degenerating into a series of txt-grunts (a kind of Crumbling Castle model for the text generation) and that young people are doing it because they "are even allowed to use text speech in exams now", conveniently (or stupidly) misunderstanding the difference between studying and using. D'oh!

But, there is an interesting argument to be had here over the potentially limiting effects of technology on our lexicon - both individual and shared - because as this new app demonstrates, predictive texting has evolved to offer us predictive messaging.

|

| Swift Key screen |

Instead

of just predicting the word we are typing, this app starts to predict

the next set of words, offering us phrases or even whole clauses, based

on what we have typed before. There's an example here.

And

it's even cleverer than it first appears because it can use your

existing style from Facebook, email and your previous messages, building

a mini-corpus of your own style and then suggesting these back to you

when it is appropriate.

So,

what's the problem? If your own style is being reinforced, basically

echoing your own lexical and grammatical choices, you might end up with

an ever-decreasing range of language choices. If, every time you type a

message, you're offered a set of choices influenced by your own database

of language, will you be railroaded into a restricted set of words?

Spray tan, fake boobs and lots of stuff that's like reem.

Paul Kerswill, top linguist and one of the team behind this blog (which has been set up to help students and teachers of A level English Language keep up with the latest research into linguistics) has written a new piece for The Sun this week about the Essex dialect and the role of The Only Way Is Essex (TOWIE) in spreading the region's twanging tones and lovely lexicon.

He takes a look at the ways in which TOWIE has popularised the adjective reem, the phrase shuuut uuup, and various other linguistic markers such as like and yous and offers a broader perspective on the ways the Essex dialect* has changed from its rural origins to a more cockneyfied sound and vocabulary.

As a (hopefully) soon-to-be Essex resident (and current Essex teacher) I've got to be careful about what I say about the Essex dialect, but as Paul Kerswill says in the article "As with any accent, an Essex voice evokes an image, or a stereotype, of a certain sort of person — you can fill in what sort" so I'll leave it at that.

There's some debate on The Sun's messageboard about where reem derives from (or whether it should actually be spelt ream). Any ideas?

And as a quick aside, here's a link to an article in today's Metro about an ATM in Leytonstone, East London (original cockney territory) which offers you a choice of languages: English or Cockney. So you can withdraw a Lady Godiva (£5) or a pony (£25), but count your notes as some of these cockneys are proper dodgy geezers.

Thanks to emagazine's Facebook page for the Sun link and Gabriel Ozon at UCL for the Metro one.

*Dialect here is being used in its broader sense of lexis, semantics, grammar and phonology (so including accent as part of it).

He takes a look at the ways in which TOWIE has popularised the adjective reem, the phrase shuuut uuup, and various other linguistic markers such as like and yous and offers a broader perspective on the ways the Essex dialect* has changed from its rural origins to a more cockneyfied sound and vocabulary.

As a (hopefully) soon-to-be Essex resident (and current Essex teacher) I've got to be careful about what I say about the Essex dialect, but as Paul Kerswill says in the article "As with any accent, an Essex voice evokes an image, or a stereotype, of a certain sort of person — you can fill in what sort" so I'll leave it at that.

There's some debate on The Sun's messageboard about where reem derives from (or whether it should actually be spelt ream). Any ideas?

And as a quick aside, here's a link to an article in today's Metro about an ATM in Leytonstone, East London (original cockney territory) which offers you a choice of languages: English or Cockney. So you can withdraw a Lady Godiva (£5) or a pony (£25), but count your notes as some of these cockneys are proper dodgy geezers.

Thanks to emagazine's Facebook page for the Sun link and Gabriel Ozon at UCL for the Metro one.

*Dialect here is being used in its broader sense of lexis, semantics, grammar and phonology (so including accent as part of it).

Monday, October 24, 2011

# hashtags - this year's LOL?

Following on from the post about changing punctuation, here's a guest post from Emma Bertouche who is an Online Marketing Executive for a language translations company and writes for several websites and blogs regarding language and social media.

Advances in technology have always added to and changed the way we use the English language. The rise of social media and the regular social network user is the latest example of the internet driving many new or distorted words and phrases into common language, infiltrating themselves into daily use in written and spoken communication.

Many blogs and articles are written every day on how this is perceived to be diluting and misusing the English language – and many other languages for that matter. One phenomenon that needs closer examination is the growing use of the lowly hashtag - ‘#’ – to emphasise an argument, feeling, or solidarity with a group.

For those people unfamiliar with Twitter and the hashtag phenomenon, words or phrases are prefixed with a hash symbol (#), with multiple words concatenated, such as:

#RealAle is my favourite kind of #beer

Then, a person can search for the string #RealAle and this tagged word will appear in the search engine results. Hashtags are used by people to try and get a topic trending. A trending topic is a word, phrase or topic that is posted (tweeted) multiple times, these trending topics are then shown on websites, including Twitter's own front page. The aim is that users can then search for any Tweets containing that specific term or phrase and read what other Twitter users across the globe are saying about it.

On the surface this seems to be another internet trend, spreading from person to person within the online culture, which originated on the Twitter social networking site. So when someone in the office recently described themselves (in the spoken word) as “hashtag smug” it was an example of how quickly the language of social media is making an appearance not only in other online communities, but also creeping into everyday spoken conversation.

The phenomenon has also been picked up by The New York Times, which wrote this interesting article about the hashtag making this way into our lives. We increasingly see instances of the hashtag being implemented on other social networks, where characters are no longer capped(the internet equivalent of shouting) yet people use it to stress a word or point that they are trying to make. Furthermore, unlike ‘text speak’ and the lingo of teenagers, this trend is not exclusive to a specific demographic of people, and can have universal appeal.

Twitter is, in essence, the 21st Century equivalent of William Tyndale, facilitating the mass distribution of the written word across an era-defining medium; in Tyndale's case, Caxton's printing press, and in the case of Twitter, social media. The messages they communicate may have been different (Tyndale translated the Bible, rather than screamed #WELOVEJUSTINBIEBER) but their aim is the same; for as many people to see their message as possible. Similar to Tyndale, however, there are many clamouring to cry heresy at the implementation of a new language variant, and opposition to the hashtag is growing to levels previously experienced as a result of the rise of texting and email. It is to be hoped those opposed don't follow Pope Clement VII's example, and seek to eradicate the problem as they see it. Thankfully, I don't think nouns are flammable.

Of course as with any form of publicity, be it self promoting or for business there can often be a downside or even a backlash at attempts to use the hashtag for marketing purposes. People often see the opportunity to use trending topics to spam Twitter with unrelated topics but then include a popular hashtag to ensure their tweet gets seen be a decent number of Twitter users. One of the more documented mistakes was that of Habitat who used hashtags including #IranElection and #Mousavi to promote discounts on their products, making for some heroically non-sensical tweets. The idea behind the madness is not a particularly clever one at the best of times but linking a range of home furniture to sensitive humanitarian crises is only ever going to anger people. .

Social media trends do not provide the first examples of ‘moral panic’ regarding language change, either. In fact, there is a long history of alarm at evolving language trends. The rise of the postcard brought with it concerns that, due to the limited amount of space people had to write their messages, the use of the English language would be compromised. Comparisons between the post card and Twitter have already been made by The Daily Mail, back in 2009.

It will be interesting to learn what future language scholars make of the introduction of social media and its effects on the spoken word – there is already debate raging on what to call this new phenomenon.

While researching the hashtag I found a web forum where linguists were asking “Is there a linguistics term for glued-together Twitter hashtags, such as #vacationwishlist, #isawesome, and #wordsthatdescribeme?” The closest answer I could find was portmanteau but a hashtag doesn’t create new words; it just lumps existing words together.

There doesn’t seem to be an agreed linguistic term for this yet, but people are still able to easily associate meaning to it. Unlike the controversy of ‘text speak’ entering the English Language, which seemed to scythe down language to its most basic construct, would the inclusion of hashtag English (as indeed with other languages that communicate via Twitter) be as contentious?

In the same way that people now question whether it is acceptable to include ‘smilies’ in emails to colleagues, the fact that the use of #hashtag is up for discussion means that some people already find it acceptable and do use them - whether others like it or not.

Although I have only heard one example of ‘hashtag’ in spoken communication, it will be interesting to see if this catches on. Social media is presenting a whole new set of questions on the future of language for the students and tutors to solve, and who knows - maybe if I was ‘down with the kids’ I wouldn’t feel so #confused .

Advances in technology have always added to and changed the way we use the English language. The rise of social media and the regular social network user is the latest example of the internet driving many new or distorted words and phrases into common language, infiltrating themselves into daily use in written and spoken communication.

Many blogs and articles are written every day on how this is perceived to be diluting and misusing the English language – and many other languages for that matter. One phenomenon that needs closer examination is the growing use of the lowly hashtag - ‘#’ – to emphasise an argument, feeling, or solidarity with a group.

For those people unfamiliar with Twitter and the hashtag phenomenon, words or phrases are prefixed with a hash symbol (#), with multiple words concatenated, such as:

#RealAle is my favourite kind of #beer

Then, a person can search for the string #RealAle and this tagged word will appear in the search engine results. Hashtags are used by people to try and get a topic trending. A trending topic is a word, phrase or topic that is posted (tweeted) multiple times, these trending topics are then shown on websites, including Twitter's own front page. The aim is that users can then search for any Tweets containing that specific term or phrase and read what other Twitter users across the globe are saying about it.

On the surface this seems to be another internet trend, spreading from person to person within the online culture, which originated on the Twitter social networking site. So when someone in the office recently described themselves (in the spoken word) as “hashtag smug” it was an example of how quickly the language of social media is making an appearance not only in other online communities, but also creeping into everyday spoken conversation.

The phenomenon has also been picked up by The New York Times, which wrote this interesting article about the hashtag making this way into our lives. We increasingly see instances of the hashtag being implemented on other social networks, where characters are no longer capped(the internet equivalent of shouting) yet people use it to stress a word or point that they are trying to make. Furthermore, unlike ‘text speak’ and the lingo of teenagers, this trend is not exclusive to a specific demographic of people, and can have universal appeal.

Twitter is, in essence, the 21st Century equivalent of William Tyndale, facilitating the mass distribution of the written word across an era-defining medium; in Tyndale's case, Caxton's printing press, and in the case of Twitter, social media. The messages they communicate may have been different (Tyndale translated the Bible, rather than screamed #WELOVEJUSTINBIEBER) but their aim is the same; for as many people to see their message as possible. Similar to Tyndale, however, there are many clamouring to cry heresy at the implementation of a new language variant, and opposition to the hashtag is growing to levels previously experienced as a result of the rise of texting and email. It is to be hoped those opposed don't follow Pope Clement VII's example, and seek to eradicate the problem as they see it. Thankfully, I don't think nouns are flammable.

Of course as with any form of publicity, be it self promoting or for business there can often be a downside or even a backlash at attempts to use the hashtag for marketing purposes. People often see the opportunity to use trending topics to spam Twitter with unrelated topics but then include a popular hashtag to ensure their tweet gets seen be a decent number of Twitter users. One of the more documented mistakes was that of Habitat who used hashtags including #IranElection and #Mousavi to promote discounts on their products, making for some heroically non-sensical tweets. The idea behind the madness is not a particularly clever one at the best of times but linking a range of home furniture to sensitive humanitarian crises is only ever going to anger people. .

Social media trends do not provide the first examples of ‘moral panic’ regarding language change, either. In fact, there is a long history of alarm at evolving language trends. The rise of the postcard brought with it concerns that, due to the limited amount of space people had to write their messages, the use of the English language would be compromised. Comparisons between the post card and Twitter have already been made by The Daily Mail, back in 2009.

It will be interesting to learn what future language scholars make of the introduction of social media and its effects on the spoken word – there is already debate raging on what to call this new phenomenon.

While researching the hashtag I found a web forum where linguists were asking “Is there a linguistics term for glued-together Twitter hashtags, such as #vacationwishlist, #isawesome, and #wordsthatdescribeme?” The closest answer I could find was portmanteau but a hashtag doesn’t create new words; it just lumps existing words together.

There doesn’t seem to be an agreed linguistic term for this yet, but people are still able to easily associate meaning to it. Unlike the controversy of ‘text speak’ entering the English Language, which seemed to scythe down language to its most basic construct, would the inclusion of hashtag English (as indeed with other languages that communicate via Twitter) be as contentious?

In the same way that people now question whether it is acceptable to include ‘smilies’ in emails to colleagues, the fact that the use of #hashtag is up for discussion means that some people already find it acceptable and do use them - whether others like it or not.

Although I have only heard one example of ‘hashtag’ in spoken communication, it will be interesting to see if this catches on. Social media is presenting a whole new set of questions on the future of language for the students and tutors to solve, and who knows - maybe if I was ‘down with the kids’ I wouldn’t feel so #confused .

Language change: big pictures and little details

Two pieces on language change that have appeared in the press recently offer us a really neat contrast between the big picture of change - David Crystal's The Story of English in 100 Words - and the very small details of it - Henry Hitchings' Wall Street Journal piece on the history and future of punctuation.

Crystal picks one hundred English words and uses them to trace a history of the language, taking in foreign loan words like potato and trek, a homegrown Celtic term like brock or a Scots one like wee, as well as many more recent ones from internet culture, abbreviations and cultural shifts.

Hitchings takes a look at punctuation: where it comes from and where it's going. He considers archaic forms like the pilcrow and hedera, ones that he thinks are on their way out like the apostrophe and semi-colon and ones that are coming back in or just appearing, the snark and the interrobang.

Both articles are a good read and offer some excellent examples of how to take a particular element of language - lexis in Crystal's case, orthography in Hitchings' - and trace its changes over time.

Crystal picks one hundred English words and uses them to trace a history of the language, taking in foreign loan words like potato and trek, a homegrown Celtic term like brock or a Scots one like wee, as well as many more recent ones from internet culture, abbreviations and cultural shifts.

Hitchings takes a look at punctuation: where it comes from and where it's going. He considers archaic forms like the pilcrow and hedera, ones that he thinks are on their way out like the apostrophe and semi-colon and ones that are coming back in or just appearing, the snark and the interrobang.

Both articles are a good read and offer some excellent examples of how to take a particular element of language - lexis in Crystal's case, orthography in Hitchings' - and trace its changes over time.

Friday, October 21, 2011

Keeping it street

There's a new wave of TV dramas and UK films on the way which feature gangs, council estates and street crime. It's not surprising that given the summer riots and subsequent moral panic about the state of our nation (and more importantly the state of our estates) these programmes are taking a look at life on the fringes for young people, but what's apparent is that for many writers and directors the key way for them to make their visions of urban Britain look and sound authentic is to get the slang right.

A clued-up young urban audience is not going to believe that the people they see on the screen are genuinely like them unless they speak like them, you get me? So, in order to keep it real they've used slang consultants - what a great job that must be.

This piece on the BBC News magazine site takes a look at some of the slang and its uses among young people, while this is a short article I did for the MacMillan Dictionary blog earlier in the week, looking at how slang gets picked up and appropriated by mainstream society.

I'm not sure how I feel about slang being seen as the one, crucial marker of authenticity, because like so many other aspects of language use, slang is about identity and more than just a series of buzzwords for outsiders to pick up and use for a while. Then again, part of the joy of slang is that it's constantly reinventing itself, with slang innovators generating new words, new meanings all the time to keep a sense of individuality and identity even as their words start to seep into the mainstream.

Maybe it's that cycle of creation - appropriation - recreation that keeps them on their toes, feeding the new slang into the system.

A clued-up young urban audience is not going to believe that the people they see on the screen are genuinely like them unless they speak like them, you get me? So, in order to keep it real they've used slang consultants - what a great job that must be.

This piece on the BBC News magazine site takes a look at some of the slang and its uses among young people, while this is a short article I did for the MacMillan Dictionary blog earlier in the week, looking at how slang gets picked up and appropriated by mainstream society.

I'm not sure how I feel about slang being seen as the one, crucial marker of authenticity, because like so many other aspects of language use, slang is about identity and more than just a series of buzzwords for outsiders to pick up and use for a while. Then again, part of the joy of slang is that it's constantly reinventing itself, with slang innovators generating new words, new meanings all the time to keep a sense of individuality and identity even as their words start to seep into the mainstream.

Maybe it's that cycle of creation - appropriation - recreation that keeps them on their toes, feeding the new slang into the system.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Heated debates: mongs, spastics and housewives

The comedian Ricky Gervais has attracted criticism from a range of quarters for his use of the word mong in recent comments on Twitter. According to Radio 1 Newsbeat and The Sun, Gervais's "jokes" have included references to himself as being monged-up when pulling a face, welcoming his followers with good monging and many more hilarious quips that demonstrate his mastery of sophisticated wordplay.

Gervais claims that the word isn't offensive and has no connection to people who suffer from Down Syndrome (who back in my school days used to - cruelly - be called mongoloids, mongols or mongs, apparently because of the facial resemblance between sufferers and Mongolian people), but he's old enough and clever enough to know that it is offensive for many many people. His argument - that language changes, get over it - is superficially attractive but ultimately disingenuous.

He knows that the word still carries connotations of abuse and is used to belittle and hurt, so why does he use it? Why not use twit, idiot or fool? And there are plenty of other ones to choose from too.

The Angry Mob blog runs a good feature on the story here and the comedian Richard Herring does a thoughtful post* about the language used to mock disabled people here:

The argument over offensive words has previously included references the golfer Tiger Woods made about playing "like a spazz" - derived from the word spastic, another term that's been used offensively in playground abuse - terms like retard (a word that landed the Black-Eyed Peas in trouble, when really they should be in jail for their utterly appalling ear pollution, rather than linguistic crimes) and the long debate over the the n-word and its reclamation.

And of course, more recently we've had a big debate over the use of the word slut as part of the slutwalk movement and a revival of arguments over the word chav and its meanings.

Even apparently inoffensive terms like housewife have come in for criticism recently, with a Mothercare survey revealing that two thirds of mothers find the term insulting. In a response to this survey, Lucy Mangan of The Guardian** looks at (not very serious) alternatives to housewife, such as milch cow and baby wrangler, but serious alternatives have been considered in the past, as this story about the Women's Institute back from 2006 shows.

So, is Gervais the victim of the old PC brigade? Are the feminazi and do-gooding liberal elite stormtroopers of the Political Correctness massive swinging into action. Has, for probably the millionth time (if you read the Daily Mail), PC really gone too far this time?

Well, what is PC? Part of the problem with the whole debate around Political Correctness is that the term itself is troublesome and contested by different groups. PC was initially connected to the women's rights movements of the 1970s and sought to draw attention to the inequalities in language that seemed to exist between men and women, changing the language to avoid discrimination and offence. It later grew to take in terms connected to race, sexuality and disability.

Words like chairman were challenged, and uses of language that seemed to exclude or marginalise women and minority groups were discussed, and alternatives proposed. Many caught on in popular usage and have not been problematic since, but others proved more contentious. So when it was noted that a sentence like "Each student must bring his notes to class" might be perceived as sexist, the alternatives "their notes", or even invented gender-neutral pronouns like "hesh", attracted ridicule or grammatical pedantry ("How can their refer to one person when it it is a plural pronoun?" they asked).

As Deborah Cameron points out in her book on language intervention, Verbal Hygiene, the term Politically Correct was initially an ironic, self-mocking label applied by some feminists to poke gentle fun at their own "right-on-ness", but within the space of a few years opponents of PC - those who opposed changing some labels which might be considered offensive or insensitive, and who were often politically right wing and reactionary - were using it as a term of abuse. In essence what the anti-PCers were arguing against was any attempt to reform the language, because they saw it as part of a radical political agenda with which they disagreed.

If the term PC is used now it's used very much as a term with negative associations. If you're PC you're humourless, probably militant and unbending in your views and more than likely want to ban Christmas and turn it into Winterval to avoid upsetting disabled lesbian Muslims. But regardless, arguments over sensitive and derogatory language usage still rage, and whether we call it PC or just linguistic sensitivity, people will still get upset about certain words and what they can mean, while others argue for their right to say anything they like.

So for this month's heated debate, where do you stand?

Can we control or influence which words are used in society?

Is it a positive step to challenge uses of words like mong and spastic?

Alternatively, is PC just a means of clamping down on freedom of expression?

Does changing language have any effect on wider social issues like racism and sexism?

Over to you...

* Thanks to @SFXEnglish for the link

** and thanks to Jon Dolton for this one

Gervais claims that the word isn't offensive and has no connection to people who suffer from Down Syndrome (who back in my school days used to - cruelly - be called mongoloids, mongols or mongs, apparently because of the facial resemblance between sufferers and Mongolian people), but he's old enough and clever enough to know that it is offensive for many many people. His argument - that language changes, get over it - is superficially attractive but ultimately disingenuous.

He knows that the word still carries connotations of abuse and is used to belittle and hurt, so why does he use it? Why not use twit, idiot or fool? And there are plenty of other ones to choose from too.

The Angry Mob blog runs a good feature on the story here and the comedian Richard Herring does a thoughtful post* about the language used to mock disabled people here:

I don't think any of them would do the same with the n-word or "p*ki" but they're happy to use "mong" or "retard" as a means of getting a laugh. And audiences will laugh at those words too and rarely even complain about them. But I think they do equate with those racial and homophobic epithets that are rarely heard these days. They do confirm the stereotype of disabled people and contribute to their further isolation in a world that already tries to pretend they don't exist.

The argument over offensive words has previously included references the golfer Tiger Woods made about playing "like a spazz" - derived from the word spastic, another term that's been used offensively in playground abuse - terms like retard (a word that landed the Black-Eyed Peas in trouble, when really they should be in jail for their utterly appalling ear pollution, rather than linguistic crimes) and the long debate over the the n-word and its reclamation.

And of course, more recently we've had a big debate over the use of the word slut as part of the slutwalk movement and a revival of arguments over the word chav and its meanings.

Even apparently inoffensive terms like housewife have come in for criticism recently, with a Mothercare survey revealing that two thirds of mothers find the term insulting. In a response to this survey, Lucy Mangan of The Guardian** looks at (not very serious) alternatives to housewife, such as milch cow and baby wrangler, but serious alternatives have been considered in the past, as this story about the Women's Institute back from 2006 shows.

So, is Gervais the victim of the old PC brigade? Are the feminazi and do-gooding liberal elite stormtroopers of the Political Correctness massive swinging into action. Has, for probably the millionth time (if you read the Daily Mail), PC really gone too far this time?

Well, what is PC? Part of the problem with the whole debate around Political Correctness is that the term itself is troublesome and contested by different groups. PC was initially connected to the women's rights movements of the 1970s and sought to draw attention to the inequalities in language that seemed to exist between men and women, changing the language to avoid discrimination and offence. It later grew to take in terms connected to race, sexuality and disability.

Words like chairman were challenged, and uses of language that seemed to exclude or marginalise women and minority groups were discussed, and alternatives proposed. Many caught on in popular usage and have not been problematic since, but others proved more contentious. So when it was noted that a sentence like "Each student must bring his notes to class" might be perceived as sexist, the alternatives "their notes", or even invented gender-neutral pronouns like "hesh", attracted ridicule or grammatical pedantry ("How can their refer to one person when it it is a plural pronoun?" they asked).

As Deborah Cameron points out in her book on language intervention, Verbal Hygiene, the term Politically Correct was initially an ironic, self-mocking label applied by some feminists to poke gentle fun at their own "right-on-ness", but within the space of a few years opponents of PC - those who opposed changing some labels which might be considered offensive or insensitive, and who were often politically right wing and reactionary - were using it as a term of abuse. In essence what the anti-PCers were arguing against was any attempt to reform the language, because they saw it as part of a radical political agenda with which they disagreed.

If the term PC is used now it's used very much as a term with negative associations. If you're PC you're humourless, probably militant and unbending in your views and more than likely want to ban Christmas and turn it into Winterval to avoid upsetting disabled lesbian Muslims. But regardless, arguments over sensitive and derogatory language usage still rage, and whether we call it PC or just linguistic sensitivity, people will still get upset about certain words and what they can mean, while others argue for their right to say anything they like.

So for this month's heated debate, where do you stand?

Can we control or influence which words are used in society?

Is it a positive step to challenge uses of words like mong and spastic?

Alternatively, is PC just a means of clamping down on freedom of expression?

Does changing language have any effect on wider social issues like racism and sexism?

Over to you...

* Thanks to @SFXEnglish for the link

** and thanks to Jon Dolton for this one

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Pragmatics: the missing link

We've done a bit on pragmatics in AS classes over the last few weeks, looking at how context often influences language and how language often depends on a grasp of context, but here's a quick round-up of ideas about pragmatics by Stan Carey which you'll definitely find helpful.

Hiding the agent

Liam Fox, the Defence Secretary who is embroiled in a scandal about his relationship with an "adviser", has made some mistakes apparently, not that he would put it that way. He would say "I accept that it was a mistake to allow distinctions to be blurred

between my professional responsibilities and my personal loyalties to a

friend". And that, as Jonathan Freedland in The Guardian says, is a pretty rubbish way of saying sorry.

Freedland's article looks closely at Fox's slippery language, particularly his abuse of the passive voice, a grammatical technique that he describes as "grammar's way of telling you somebody is hiding something", which is a neat turn of phrase. It's a good bit of textual analysis and something that would make a sound starting point for a language investigation.

Freedland's article looks closely at Fox's slippery language, particularly his abuse of the passive voice, a grammatical technique that he describes as "grammar's way of telling you somebody is hiding something", which is a neat turn of phrase. It's a good bit of textual analysis and something that would make a sound starting point for a language investigation.

Thursday, October 06, 2011

Heated debates 2: the sequel

Thanks to everyone who contributed to the debate on gender and language variation. There'll be another heated debate coming up next week, this time on Political Correctness and language engineering.

This topic ties in with Language Change for A2 AQA A and AQA B, and also for Language Interventions (AQA A) and Language Investigations (AQA B).

If you've got any suggestions for links to articles or have any ideas to kick this off, please post them as comments.

This topic ties in with Language Change for A2 AQA A and AQA B, and also for Language Interventions (AQA A) and Language Investigations (AQA B).

If you've got any suggestions for links to articles or have any ideas to kick this off, please post them as comments.

Thursday, September 29, 2011

New blog for English Language A level teachers and students

Sue Fox and Jenny Cheshire at Queen Mary University, London have set up a new blog to help students and teachers of A Level English Language. It's called the Linguistics Research Digest and is part of their From Sociolinguistic Research to English Language Teaching ESRC Knowledge Transfer Project (more details of which can be found here).

The blog features accessible summaries of recent research in linguistics and offers a way into some of the most relevant areas of recent study. Their plan is also to set up a resource site to run alongside the blog, but for the time being there's already some very useful material on there for teachers and students alike.

The blog features accessible summaries of recent research in linguistics and offers a way into some of the most relevant areas of recent study. Their plan is also to set up a resource site to run alongside the blog, but for the time being there's already some very useful material on there for teachers and students alike.

That's cool. No, that's kewl

The OED's latest online update has ruffled a few prescripivist feathers (again) by including kewl, "an affected or exaggerated pronunciation of cool".

A few months ago, elderly wing commanders in Surrey (and other Telegraph readers) were appalled to discover that the OED had included internet acronym LOL and vaguely blasphemous initialism OMG in its pages, so it's not as if the OED isn't used to causing a bit of controversy. But as Graeme Diamond, chief editor of new words, explains, adding words to the OED is not about trying to change the language but reflect actual usage: "You have to show that the word has been in usage for a decent length of time and, most importantly, that the word is used and understood by a wide audience".

Cool itself, in its original spelling, is a tenacious piece of slang that has been knocking around for a very long time, much longer than its groovy and rad brothers as the slightly unscientific but helpful graphic on the right shows.

Michael Quinion has written about cool's development as a slang term here, and there's more from the British Library here, but it's clear that if cool is still evolving, with new uses and spellings, it's a healthy word in a healthy language.

A few months ago, elderly wing commanders in Surrey (and other Telegraph readers) were appalled to discover that the OED had included internet acronym LOL and vaguely blasphemous initialism OMG in its pages, so it's not as if the OED isn't used to causing a bit of controversy. But as Graeme Diamond, chief editor of new words, explains, adding words to the OED is not about trying to change the language but reflect actual usage: "You have to show that the word has been in usage for a decent length of time and, most importantly, that the word is used and understood by a wide audience".

|

| from http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/107/next-essay-sidebar.html |

Michael Quinion has written about cool's development as a slang term here, and there's more from the British Library here, but it's clear that if cool is still evolving, with new uses and spellings, it's a healthy word in a healthy language.

Friday, September 23, 2011

Learn some proper Gypsy rokker, mush

With the Dale Farm eviction set to take place today, Gypsy life and culture is again in the spotlight, but this BBC Kent article takes a look at Gyspy language contributions to English, contributions that go back a long way and are quite deeply embedded in our common language.

A couple of these - mush and cushti - were just normal English slang as far as I was concerned growing up in Wiltshire in the 1980s and it didn't really cross my mind that it was Gypsy dialect/slang until much later.

This page from the BBC Voices site gives a bit more detail about the roots of Romany/Gyspsy/traveller dialects while this 1897 Dictionary of Slang, Jargon and Cant features some great examples from Gypsy and other non-standard varieties.

A couple of these - mush and cushti - were just normal English slang as far as I was concerned growing up in Wiltshire in the 1980s and it didn't really cross my mind that it was Gypsy dialect/slang until much later.

This page from the BBC Voices site gives a bit more detail about the roots of Romany/Gyspsy/traveller dialects while this 1897 Dictionary of Slang, Jargon and Cant features some great examples from Gypsy and other non-standard varieties.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Debate of the month: gender and language variation

One of the big topics for debate in English Language A level in recent years has been over whether women and men communicate differently. Since the early 1970s, with the publication of Robin Lakoff’s Language and Woman’s Place , there has been plenty of focus on what might be termed “women’s language” but as Lakoff herself was quick to point out, her observations weren’t based on empirical studies (systematic data collection) but “(data)... gathered mainly by introspection: I have examined my own speech and that of my acquaintances, and have used my own intuitions in analyzing it”.

Lakoff’s observations included some that have made it into pretty much every A level student’s (and teacher’s) list of key facts about gender and language: women use more precise colour terms, more tag questions and more evaluative adjectives than men. But of course, without any actual data to back these claims up, it was hard to work out whether what Lakoff was saying was perceptive and new or just the recycling of fairly standard stereotypes.

While Lakoff herself made some powerful points about the ways in which girls are socialised to behave in ways that are viewed as linguistically female - not talking rough or appearing "unladylike" - other linguists focused a little more on the conversational interactions between men and women. Some chose to look at interruptions and the dominance of men and submissiveness of women in conversational interaction (like Zimmerman and West – pdf here - in 1975), others at power and status (O’Barr and Atkins - summary here – in 1980), before Maltz and Borker (1982) started looking in a bit more detail at the ways in which men and women are socialised into different gender roles and how this might affect language patterns.

This was an approach that led to Deborah Tannen’s work – subsequently referred to as the Difference Model - and her bestselling book You Just Don’t Understand (Tannen talks about it here).

Tannen’s approach focussed on what she called the “cross-cultural communication” between the genders:

However, Tannen’s approach came in for criticism from some for its broad-brush approach to gender, and the industry spawned by the Tannen book – John Gray’s Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus being one big seller – dumbed everything down to a new low.

Elsewhere, Jennifer Coates produced masses of work on the dynamics of spoken interaction in her excellent books Women Talk and Men Talk, pinning down the details of talk among and between the sexes and interpreting the results with an open mind. It’s about as far removed from the hippy dippy generalisations of John Gray as you can get.

More recent work on gender and language has taken one of two approaches. With advances in neuroscience, some commentators have started to look at how certain characteristics might be hard-wired into us and how men and women might just be built genetically in certain ways that we can’t avoid.

This approach has attracted criticism – this article by Madeline Bunting of The Guardian is really good – and linguists such as Deborah Cameron have argued that gender is just one factor in many that might affect our conversational styles, and that anyway, there are more differences between different men or different women (within the sexes) than there are between most men and women.

Her excellent Myth of Mars and Venus lays into the gender difference industry with an accessible overview of research and an argument that suggests it’s not only women who suffer from the obsession with different speech styles, but men too.

So, over to you. What has your own study and research suggested about gender and language variation? Are you about to embark on an A2 Language Investigation into gender? If so, what are you going to look for and why?

Lakoff’s observations included some that have made it into pretty much every A level student’s (and teacher’s) list of key facts about gender and language: women use more precise colour terms, more tag questions and more evaluative adjectives than men. But of course, without any actual data to back these claims up, it was hard to work out whether what Lakoff was saying was perceptive and new or just the recycling of fairly standard stereotypes.

While Lakoff herself made some powerful points about the ways in which girls are socialised to behave in ways that are viewed as linguistically female - not talking rough or appearing "unladylike" - other linguists focused a little more on the conversational interactions between men and women. Some chose to look at interruptions and the dominance of men and submissiveness of women in conversational interaction (like Zimmerman and West – pdf here - in 1975), others at power and status (O’Barr and Atkins - summary here – in 1980), before Maltz and Borker (1982) started looking in a bit more detail at the ways in which men and women are socialised into different gender roles and how this might affect language patterns.

This was an approach that led to Deborah Tannen’s work – subsequently referred to as the Difference Model - and her bestselling book You Just Don’t Understand (Tannen talks about it here).

Tannen’s approach focussed on what she called the “cross-cultural communication” between the genders:

For women, as for girls, intimacy is the fabric of relationships, and talk is the thread from which it is woven. Little girls create and maintain friendships by exchanging secrets; similarly, women regard conversation as the cornerstone of friendship. So a woman expects her husband to be a new and improved version of a best friend. What is important is not the individual subjects that are discussed but the sense of closeness, of a life shared, that emerges when people tell their thoughts, feelings, and impressions.

Bonds between boys can be as intense as girls', but they are based less on talking, more on doing things together. Since they don't assume talk is the cement that binds a relationship, men don't know what kind of talk women want, and they don't miss it when it isn't there.

Boys' groups are larger, more inclusive, and more hierarchical, so boys must struggle to avoid the subordinate position in the group. This may play a role in women's complaints that men don't listen to them. Some men really don't like to listen, because being the listener makes them feel one-down, like a child listening to adults or an employee to a boss.

However, Tannen’s approach came in for criticism from some for its broad-brush approach to gender, and the industry spawned by the Tannen book – John Gray’s Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus being one big seller – dumbed everything down to a new low.

Elsewhere, Jennifer Coates produced masses of work on the dynamics of spoken interaction in her excellent books Women Talk and Men Talk, pinning down the details of talk among and between the sexes and interpreting the results with an open mind. It’s about as far removed from the hippy dippy generalisations of John Gray as you can get.

More recent work on gender and language has taken one of two approaches. With advances in neuroscience, some commentators have started to look at how certain characteristics might be hard-wired into us and how men and women might just be built genetically in certain ways that we can’t avoid.

This approach has attracted criticism – this article by Madeline Bunting of The Guardian is really good – and linguists such as Deborah Cameron have argued that gender is just one factor in many that might affect our conversational styles, and that anyway, there are more differences between different men or different women (within the sexes) than there are between most men and women.

Her excellent Myth of Mars and Venus lays into the gender difference industry with an accessible overview of research and an argument that suggests it’s not only women who suffer from the obsession with different speech styles, but men too.

So, over to you. What has your own study and research suggested about gender and language variation? Are you about to embark on an A2 Language Investigation into gender? If so, what are you going to look for and why?

- What do you think of the whole debate?

- Is it helpful to generalise about how men and women communicate or should we always look at specific contexts?

- In your experience, do men and women, boys and girls talk differently?

- If so, why might this be and how does it show itself in what they say and how they say it?

- If not, what do you see happening instead?

- How different are the speech styles within one gender group? Do all boys share similar speech characteristics....girls, football, beer and..err...meat?

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Quick and dirty

Just a few quick links to really good new language stuff that might be exciting for you.

How awesome changed and grew

How "Britishisms" started to invade the USA

Why slang is a sign of a healthy language

Enjoy!

How awesome changed and grew

How "Britishisms" started to invade the USA

Why slang is a sign of a healthy language

Enjoy!

Friday, September 16, 2011

Stoking up spelling trubble

Does spelling matter? Residents of Stoke-on-Trent seem to think so, because they're worried that people will think they're thick if they see the name of their new shopping development.

This report from the BBC News website suggests that some locals feel that the name will reflect badly on them, while the agency behind the name thinks it gives the development "stand out quality"...maybe like the "stand out quality" of turning up to a funeral in pink lurex batty-riders, or declaring that your football team's new strip will be birthday suits.