I started writing this post nearly a year ago while arguments were raging over the Key Stage 2 grammar tests. At the time, feelings were running high (yes, over grammar...) and I didn't want to stick my oar in and make matters worse, so I've come back to it and tried to look at the argument in slightly different terms, with more of a focus on how it relates to A level English Language.

The teaching of grammar is not necessarily at the top of the list for topics that will interest A-level students reading this blog; after all, you're studying it already as part of this course, so do you really want to find out the gory details of how teachers and educators argue about it?

Well, maybe... and the debate about how grammar is taught is quite closely connected to some of the big language debates covered in your course: arguments over Standard and non-Standard English, the importance of understanding how language works and who has the right to tell us what is 'right' or 'wrong'. All that stuff. So, you might want to read on, if you're a student.

Shots have been fired recently (and since it was all initially proposed) over the test taken by pupils in Year 6 at Primary Schools as part of what have been called the Key Stage 2 SPaG tests (Spelling, Punctuation and Grammar) but have more recently been named the GPS tests (Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling), perhaps to reflect the renewed focus on grammar (first, not third, in the list).

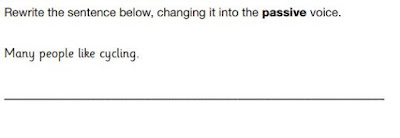

The test features some quite demanding questions about grammar, including some of the following:

|

| source: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/327332/2014_KS2_L6_English_GPS_short_answer_booklet_DIGITALHO.pdf |

How would you do on these? Well, you might want to

try them yourself and check the mark schemes that are available to the public.

Why is there an argument over this test and why should it matter to you? Because politics. Grammar is political.

It's not

purely about politics and that is one of the first points to make about this, because much of the debate between linguists, teachers and educationalists has actually been about the grammar of the grammar tests, and more precisely the amount of grammar that a 10 year-old should be learning, why they should be learning it and what they should be doing with that grammar. Linguists disagree to some extent over how important it is to teach grammar and the meta-language of grammar (i.e. the grammatical terminology) to school students and there are good arguments from both sides of the debate about this. But grammar is also very political, because it is used by politicians to signal their attitudes to a range of other things.

Deborah Cameron, who is perhaps better known recently for

her ace language blog and excellent

The Myth of Mars and Venus, wrote an important book in 1995 called

Verbal Hygiene. In this, she argued that much of the debate around grammar in the media back in the 1980s and early 90s - when last there was a big bust-up over it - was tied up very closely, not so much with language, but with morality and social cohesion, and the threat of imminent social collapse that was pinned by many conservatives on the permissive 1960s and their anything goes attitude to sex, drugs and err...grammar.

Grammar had been a part of English teaching for many years but had started to fall by the wayside in the late 1960s and early 1970s. By the time I was at secondary school in the 1980s (ironically, at a grammar school, where very little grammar was taught outside French and German lessons), grammar was off the menu.

By restoring grammar teaching to the English curriculum, the government of the time could show a return to academic rigour and old-fashioned virtues of correctness. The certainties of grammar - where there is (supposedly) a clear right and wrong - would take the place of the limp-wristed liberalism of the 1980s classrooms where communist teachers and perfumed fops (or skanky goths, in my case) would discuss poetry and feelings with barely a mention of a clause or phrase. That was one view anyway...

According to Cameron, the desire to get grammar back on the agenda was about much more than just language:

Grammar was made to symbolise various things for its conservative proponents: a commitment to traditional values as a basis for social order, to ‘standards’ and ‘discipline’ in the classroom, to moral certainties rather than moral relativism and to cultural homogeneity rather than pluralism. Grammar was able to signify all these things because of its strong metaphorical association with order, tradition, authority, hierarchy and rules.

It was interesting that these seismic rumblings about grammar should have resonated so powerfully in the 1980s, because it was a time of turbulence in education, with the birth of the National Curriculum, but also a time of political and social upheaval brought about by a right-wing Conservative government. And that's where there's a link to what is happening with grammar today.

Another right-wing Conservative government is in power. Tests must be 'rigorous' because 'rigour' is what works. Tests are vital because how else do we judge schools and teachers? How else do we feed data into league tables that tell us which school is doing better than another? Well, it doesn't have to be like this, but that's another issue entirely.

When Michael Gove - then the Minister for Education - set about creating a new literacy test for Key Stage 2, he definitely wanted grammar at the heart of it. He hated the kind of English lessons where you would study the language of online communication or spoken conversations and longed for Victorian novels and the thwack of tough, hard, rigorous grammar on his soft... sorry, getting carried away there, but you get the picture. He wanted nouns, verbs, adjectives, noun phrases, relative clauses, the present progressive and the passive voice to feature in the tests. But most of all, he wanted the subjunctive mood: a piece of grammar that has been in decline since the Nineteenth Century.

And if these sound like the kinds of things you learn at A level, that's because they are - and I like to think we make quite good use of them in how we analyse and discuss language. But for Key Stage 2, when children are 10-11 years old?

At the same time, grammar also provided Gove with a way of assessing a slippery subject. As anyone will tell you, English can be very subjective. I might analyse a poem and see an extended metaphor for the tragic decline of a long-term relationship; you might read the same poem and see it as a few images about candles being snuffed out to prevent a fire. English has *all* the feels. But grammar... well, that's nearly like maths, or some some might argue, at least.

So, let's take this back to what it all has to do with A level English Language. You might not start the course looking at arguments about standard and non-standard uses of English, or the importance of 'correct' grammar, but you'll certainly move onto those at some point, and the debates are perennial and often very heated.

Modern linguists have generally taken a position that might be defined as

descriptivist: they study language,

describing its features, its functions and (sometimes) its users and what they might be doing with it.

On the other side, there's often been a position held by conservatives (sometimes conservatives with a little 'c', sometimes conservatives with a big 'C' and sometimes conservatives who are - quite frankly - just complete 'C's) that tells us language should not change too quickly, that old is best and that grammar is all about following rules and being right or wrong. This is generally called

prescriptivism because it's an approach that prescribes "good English" to us in the same way a doctor might prescribe medicine to make us better.

The trouble is - as nearly every linguist will tell you - language always changes. The history of English is one of change, and grammar has changed a great deal. Just look at the pronoun system and what Old English used before Old Norse added to it (clue: the Vikings didn't just

like 3rd person plural pronouns: they

loved them).

And then have a look at the disappearance of

thee and

thou (in Standard English usage, at least, not in far-flung corners of Yorkshire or Kaiser Chiefs lyrics). Word order is another area of huge change - in the general syntax we use for most structures in modern English, but especially in how we form questions. If grammar changes more slowly than other aspects of language - and linguists are generally agreed that this is the case - it still changes and those changes stack up over time.

The other aspect of all of this is that the so-called 'rules' of English grammar are often not that at all; they are conventions, agreed upon by users of language and therefore susceptible to change. As

an article a week or two back about the split-infinitive pointed out, this supposed error in English grammar was always a dubious rule to follow.

So, if grammar changes and grammar rules can be questioned, can we really place such high importance on teaching "correct" grammar? Yes and no. The debate about the grammar tests at Key Stage 2 shouldn't be about whether grammar is a good thing or a bad thing to learn and understand. I'll be clear about my own view: it's definitely a good thing. I think we need to understand the system of our own language and be able to describe its elements to explain how it works and see what we can do with it. And we also need a shared grammar to understand each other - that's why Standard English exists and one of the reasons why it's valued.

But what kind of grammar should be taught? The prescriptive kind doesn't really work when you live in a world of change. It might be attractive to a certain kind of person because it symbolises an adherence to tradition and offers the possibility that change can be stopped or at least slowed down, but I don't really buy that view. The problem with a prescriptive approach to grammar is often that it goes beyond what grammar really is (word classes, clauses, phrases and all that stuff) and into the policing of all forms of language - accents, dialects, slang and even body language and tone of voice.

It's instructive, I think, that at the same time Gove was introducing the grammar tests for 10 and 11 year-olds (even taking such an interest that he insisted his own favourite, the

subjunctive mood appeared in the tests, against the advice of actual linguists on his expert panel) he was also getting rid of spoken language and electronic texts from the GCSE syllabus (and replacing them with 19th Century novels).

Why should that matter? Surely, great literature is more important to study than some

"tape recordings of Eddie Izzard and the Hairy Bikers"? Well, it doesn't have to be either/or. There *has* to be a place for studying language in all its forms, not just its most respected and long-lasting ones.

Other forms of language need to be studied too, you know... the actual language we use nearly all the time and from which we might gain something really useful.

But all of this is part of a bigger picture; a picture in which grammar is about rigour, correctness, tradition and hard knowledge. And that's where we come back to A level English Language study. When people argue about language, it's often not really language that they are arguing about at all. As Milroy and Milroy put it back in 1985 in their excellent

Authority in Language:

Language attitudes stand proxy for a much more comprehensive set of social and political attitudes, including stances strongly tinged with authoritarianism, but often presented as ‘common sense’.

Henry Hitchings, author of

The Language Wars, made a similar point in a slightly different way:

These debates quickly become heated because they involve people’s attitudes to – among other things – class, race, money and politics.

So, next time you look at a debate about accent, dialect, texting 'ruining' language, emojis dumbing us all down or how vocal fry makes women sound stupid and immature, just remember that it might appear to be a debate about 'just' language, but it's probably got deeper roots, and it often pays off to understand the wider agendas at work.